This in a state whose total energy production surpasses that of the second and third producers combined (Pennsylvania and Wyoming), according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Texas leads the nation not only in oil and gas production but in electricity generation too, and it is the country’s largest producer of wind power.

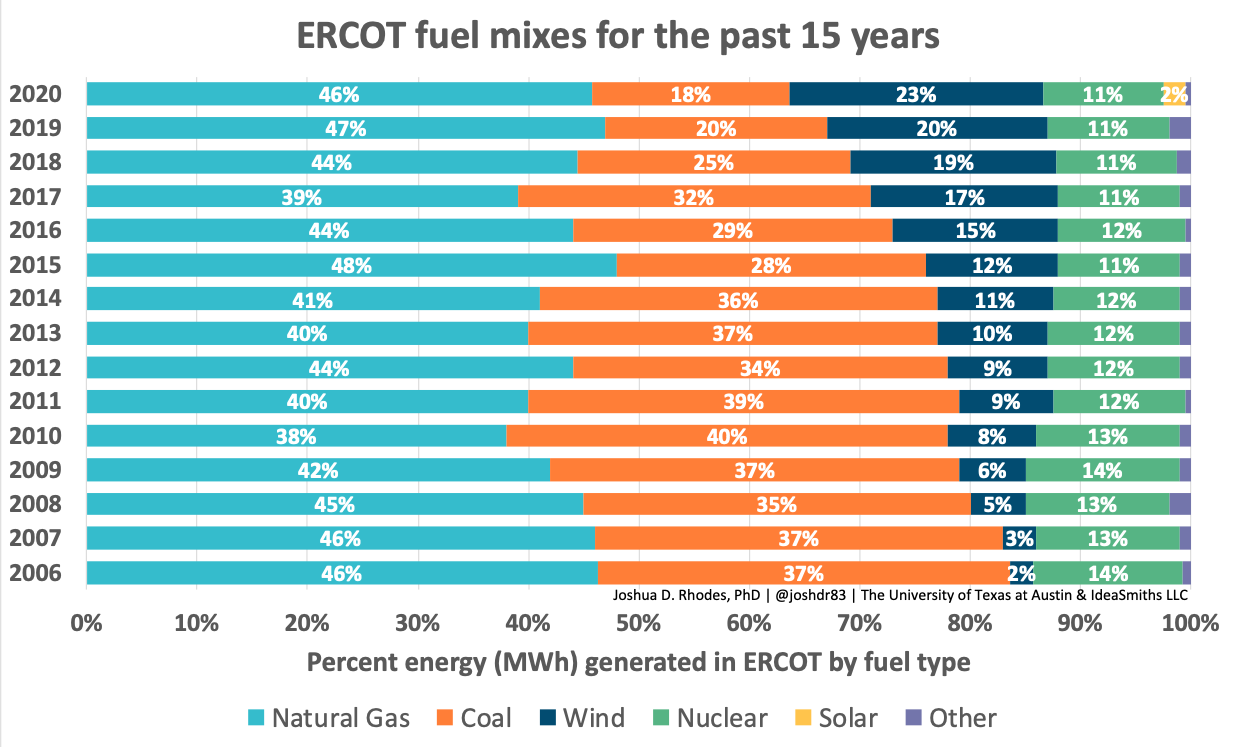

According to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT)—the grid operator that manages the flow of electricity to more than 26 million people in the state (90% of the electric load)—natural gas accounted for nearly half the electricity produced in 2020. Wind was the second fuel source used for power generation, followed by coal and nuclear, with solar in a distant fifth place.

Although Texas Governor Greg Abbott was quick to blame wind power for the crisis, many energy experts pointed to problems across the board. “Every one of our sources of power supply underperformed,” Daniel Cohan of Rice University tweeted. “Every one of them is vulnerable to extreme weather and climate events in different ways.”

In separate interviews with the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA), two experts noted that the grid operator would not have been counting on wind as the go-to fuel source under the weather conditions that hit Texas last month.

“We expected the gas was going to be there and it wasn’t. With the wind, we didn’t expect it to be there and it wasn’t,” explained Emily Grubert, Assistant Professor at the Georgia Tech School of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Because extreme temperatures can produce “wind drought,” energy planning does not assume that large amounts of wind power will be available in these types of events, said Joshua Rhodes, Research Associate with the Webber Energy Group at the University of Texas at Austin. As he put it, “I don’t rely on my sandals to keep my feet warm in the winter. That’s why I have boots.”

Still, even when measured against the lower expectations, wind did not perform as well as it should have, Rhodes said—in part because some of the turbines iced up. Texas usually worries more about summer heat than winter cold, he said, so wind turbines there tend to be outfitted with equipment to cool down the gearboxes and generators when necessary, not warm them up.

Clearly, other regions with much colder conditions than Texas have wind turbines that operate just fine, and the same holds true for natural gas, coal, and nuclear plants, according to Rhodes. That’s because in those areas, he said, the units are equipped for extreme cold and in Texas they are not.

Some of the lessons from last month’s energy crisis in Texas can resonate well beyond the Lone Star State. First and foremost, everybody needs to get much better at planning for and reacting to these types of emergencies, because they’re “absolutely” going to keep happening, said Emily Grubert, who teaches at the Georgia Tech School of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

“At the same time that we have the biggest demand on the natural gas system that we’ve ever had, supply was also cut, so it led to cascading issues across both infrastructures,” Rhodes said.

The natural gas problems even spilled over into Mexico, which depends heavily on imported gas from Texas to generate electricity. With the cutoff of the gas supply, many plants in northern Mexico were left without fuel, and millions of customers around the country experienced rolling blackouts.

In Texas, meanwhile, the grid operator was working to avoid catastrophe. In an electric power system, supply and demand must be kept in tight balance to maintain the right frequency. Because supply could not keep up with demand in this case, ERCOT started ordering the utilities in the system to shed load—in other words, to switch off the power to whole groups of their customers.

Although the plan was to rotate these outages, Rhodes said, the supply was so low that by the time the most critical circuits were covered (areas that included hospitals, fire and police stations, and other essential services) there was no more power to allocate. That left more than 4 million utility customers—some 12 million people, according to Rhodes—without electricity for as long as four days, in the bitter cold.

“I would hope that every energy source would be better at this going forward, because we can’t have that happen again,” he said.

As bad as the situation was, it could have been even worse. ERCOT President and CEO Bill Magness told reporters that at one point, the grid was “seconds and minutes” away from total collapse, and that if that had happened, it could have taken weeks or even months to restore power to everyone. (ERCOT’s board voted in early March to dismiss Magness.)

Texas may have escaped the worst-case scenario, but it did not escape real pain. Press reports have blamed the storm or the blackouts for as many as 50 deaths, and countless people endured hardship. Some burned wooden furniture to try to get warm. The public water supply was compromised in some cities. Families without heat saw their water pipes freeze and burst, causing extensive damage.

“Literally, for many people, their ceilings have fallen down. Homes have been destroyed,” Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner told National Public Radio. “A lot of people don’t have insurance. They don’t have the financial means.”

Texas is no stranger to cold weather; in fact, an arctic cold front that hit the state almost exactly a decade ago—in early February 2011—produced similar problems, though that event was less severe.

Temperatures last month not only were considerably colder than they had been a decade earlier, but they also lasted longer and covered the entire state. In testimony before a legislative committee on March 1, the head of ERCOT said the maximum generation that needed to be shed this time around was more than 3.5 times as in 2011.

A 350-page report on the earlier event analyzed the causes and proposed a range of recommendations, including winterization measures. The report, prepared by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, noted that previous cold-weather events had happened in the Southwest in six previous years since 1983, with varying degrees of severity.

It’s unclear how many of the report’s recommendations were ultimately followed in Texas. In the state’s largely deregulated electricity market, Rhodes said, it would have been up to each company to determine whether it might be cost-effective to implement recommended changes.

“There’s no capital recovery method built into our system that would allow them to recover those costs,” he said. In this case, companies that had invested in winterization and were able to keep producing power throughout the crisis would have made a lot of money, because energy prices soared to astronomical levels; however, they would not have been penalized if they had not made the investments. “It’s all carrots and no sticks,” Rhodes said.

The state’s deregulated environment has come under fire from many quarters in the wake of the Texas outages. “Deregulation was something akin to abolishing the speed limit on an interstate highway,” Ed Hirs of the University of Houston told the New York Times. “That opens up shortcuts that cause disasters.”

On the flip side, deregulation has helped drive the rapid development of renewable energy in Texas, because it’s much easier and faster to build power plants and connect them to the grid than in many other places, according to Rhodes.

He’s not convinced that Texas would have fared much better in this particular situation with a more regulated system. ERCOT calculated how much capacity the grid would need during the storm and thought that plenty of power plants were available to supply it. “It hasn’t been proven to me that a regulated entity would have forecasted an event like this better,” he said.

“It’s really easy to say they should have planned for events like these,” Rhodes continued. “I wonder if they would have been laughed out of the room if they had planned for everything going wrong at the same time.”

One vulnerability highlighted by the storm, Rhodes said, is how “coupled” the electricity and natural gas sectors are in Texas. Not only do half the state’s power plants burn natural gas, but about 40% of homes and business depend on gas for heating. The two sectors are overseen by different state commissions and there is no oversight agency compelling them to work together.

Another aspect of the power system in Texas that has garnered a lot of attention since the storm is the state’s independent electric grid. In most of the United States, electric utilities are connected to one of two large regional transmission grids covering East and West; these interconnections allow them to purchase power from far away if they need to.

Texas, however, operates its own grid, for reasons related to history, geography, technology, and politics, as Rhodes explained. Initially, he said, the state’s grid evolved somewhat naturally, with connections between major population areas and not a lot of infrastructure around the far-flung edges, which tend to be more rural. Then, as federal laws started to regulate electric grids, Texas “figured that if we kept it within our borders we wouldn’t be under federal jurisdiction,” Rhodes said.

He believes that connections to other grids would have helped Texas get through the latest crisis “a bit easier” though probably not escape it altogether. After all, some neighboring states had their own problems with outages during the storm.

Texas is so big and geographically diverse that in most cases, one part of the state could pull resources from another to deal with unusual circumstances, said Emily Grubert. This time, though, the entire state was in trouble.

“When people talk about connectivity, it’s less about whether you’re connected to other states and more about whether you have access to enough geographic variability that you can overcome big weather events like this,” she said.

The long process of sorting out what happened and why and what should be done about it is now well underway in Texas. Lawsuits have been filed, hearings held, bankruptcies declared, resignations accepted.

One major outstanding issue is what to do about huge unpaid electric bills. As the system’s financial clearinghouse, ERCOT bills energy retailers for the power they use and then passes the money on to the generation companies that produced it. However, retail electricity providers now owe generators large amounts of money, and consumers may have to cover that over the long term, Rhodes said.

Some consumers have already experienced sticker shock. People who had opted for variable-rate power contracts tied to wholesale electricity prices were billed thousands of dollars for the small amounts of electricity they were able to use when prices were at their highest.

Whether policy makers in Texas will decide that something should be done to prepare for this sort of event in the future will depend in part on how often they think such a situation might arise, Rhodes said.

“Making an argument based on climate change for this would be harder, I think, than making an argument based on what we just saw,” he said. “It’s going to come down to, do you believe it’s going to happen again in the near term, or long term, and how much are you willing to pay to deal with it?”

“We are going to see more extreme events that are outside of design parameters across the country and across the world,” she said.

Whether or not the polar vortex that brought below-freezing temperatures to Texas was a direct result of climate change—the science is still out on that, Grubert said—there’s no question that a changing climate will introduce more unpredictability and more risk into energy systems.

“How you manage that risk and how you design your system to fail safely is a huge part of the process of engineering,” she said.

Underinvestment in energy infrastructure has been a chronic problem everywhere, Grubert said. “A lot of time we design infrastructure to last for 30 years and then run it for 100,” she said. Add in a lack of maintenance and the challenges of a changing climate, and “you have a pretty serious recipe for disaster.”

But, she said, this is an exciting time in the energy sector, with the move toward different types of fuel and the chance to rethink whole systems and figure out better ways to operate. “It’s much, much easier to design around resilience and to think about what you actually want your system to be able to do at the beginning,” she said. “With the decarbonization process, we have the opportunity to design a grid that does what we need it to do.”

Beyond the energy system itself, though, Grubert would like to see more efforts to prepare for emergencies like the one in Texas. If buildings were better insulated, for example, people would be better able to weather extreme temperatures, both hot and cold. And having sufficient shelter available for an event like this is also important. The focus should be not only on technical matters like grid frequency, she said, but on whether people are warm.

“It’s not just about the grid. It’s really making sure that everybody has access to safe and reliable services.”

View Map

View Map