Surinamese President Chandrikapersad “Chan” Santokhi talked about the road ahead for his country at an energy conference held last month in Georgetown, Guyana.

“It is not only that we must transition from one energy to a cleaner and renewable one, but also we must consider how energy itself will transform our lives and economies as we go forward,” he said, according to local press reports.

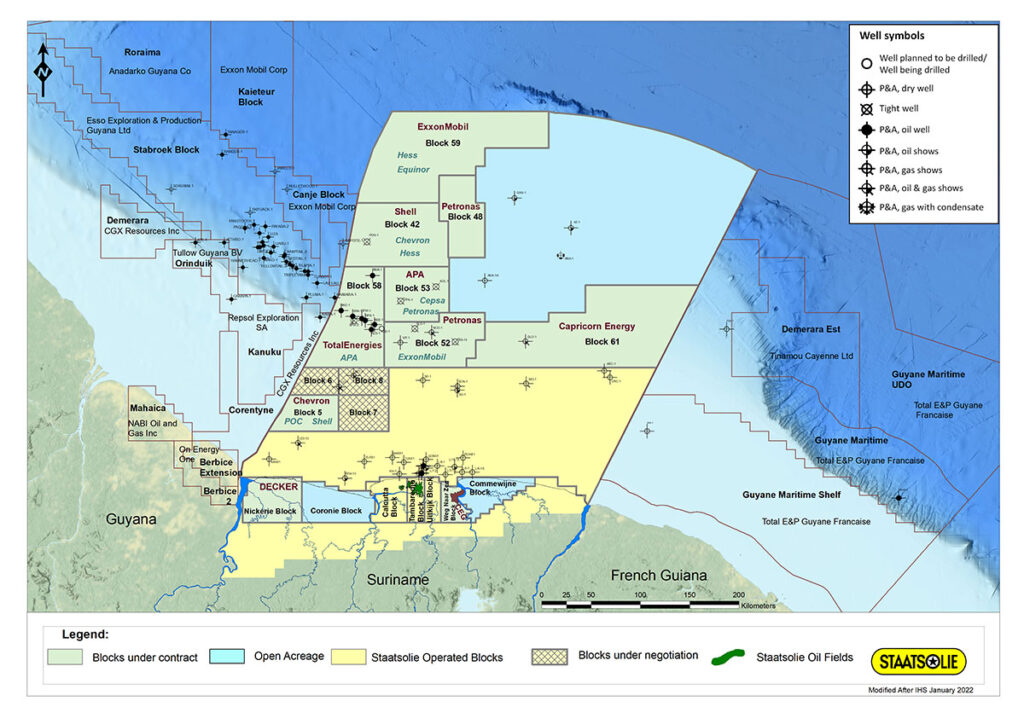

Successive oil discoveries in the waters off Suriname and Guyana have caused the world to take notice in recent years. A headline last year on the energy news site Oilprice.com put it this way: “The Guyana-Suriname Basin Could Be The Last Big Oil Boom.” Guyana has already started to produce oil, and offshore production in Suriname has been projected to begin in 2025.

Offshore oil wells in the Guyana-Suriname Basin | Credit/source: staatsolie.com

In his recent remarks in Georgetown, Santokhi said that the two South American neighbors “have a historic and unique obligation to manage their oil resources well, with adherence to internationally recognized and accepted environmental standards.” And he stressed that both countries are on a path to a sustainable energy future, transitioning from carbon-based energy to green energy.

“The question now,” he said, “is how do we make that transition utilizing our newfound resources wisely with modern technology to lay a solid foundation for a more diversified economy for generations to come?” Santokhi talked about oil as a tool to “help mitigate global energy poverty.”

“In charting this transition, we must recognize that others have gone before us and have profited from the revenues to develop a modern economy and create a future path of economic development where oil and gas may not play a significant role anymore,” he said.

Chandrikapersad “Chan” Santokhi, President of Suriname, at COP26 climate conference in Glasgow | Credit/source: CARICOM

That tension between the need for development and the need for the world to move away from fossil fuels also came through in the Surinamese head of state’s remarks at last year’s COP26 climate conference in Glasgow. He expressed strong commitment to the green energy transition and stressed that climate mitigation and adaptation policies were especially important for a low-lying coastal country like his own. Although he did not mention oil directly, he referred to the need for “a balanced approach, because we must recognize the different levels of development in a historical perspective.”

“We see double standards creeping in our thinking, whereby those who have already benefited from carbon-driven economies would like to prevent emerging economies to lay a similar foundation for the political stability, social development, and economic prosperity,” Santokhi said.

Forest around Lake Brokopondo, Suriname

Today, Suriname is a net-zero country—one of only three in the world (along with Panama and Bhutan) classified as carbon-negative because they absorb more carbon than they emit. Suriname’s carbon-negative status is mainly due to its dense forests, which cover around 93% of the country, according to Minister of Natural Resources David Abiamofo.

“Our forests are of utmost importance,” he told the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA), “and with the National Forest Policy of Suriname, we are trying to maintain the density of the forest, without curbing development in the country.”

The same forest cover that is so beneficial to the environment has made it challenging to provide access to affordable and clean energy for everyone. Although around 98% of Suriname’s population has access to electricity, that is not necessarily the case for rural villages in the interior parts of the country known as the Hinterland.

Close to 110 villages still lack access to reliable electric power, Abiamofo said at the Fifth ECPA Ministerial Meeting, held last month in Panama. He said Suriname hopes to secure access to energy for all—in line with Sustainable Development Goal 7—by 2025 or 2026.

“Energy should be accessible but also affordable for everyone living within the borders of the country,” he said, “and the mission of the government for the energy sector is ensuring continuous availability of affordable and reliable energy for the total population of Suriname and for the country’s projected economic growth.”

With the support of partners such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the government of India, Suriname has begun to install mini solar power grids in many villages in the interior, Abiamofo said.

These villages, mainly Maroon and indigenous communities, have tended to rely on fossil fuel-powered generators to provide a few hours of electricity every day. Providing access to clean power 24/7 will open up opportunities for improved living conditions and the development of the social and human capital of these disadvantaged areas, Abiamofo said in response to questions from ECPA.

First solar plant for rural electrification purposes in Suriname, inaugurated in 2018 | Credit/source: Jordi Abadal Colomina

The Minister of Natural Resources told his counterparts in Panama that Suriname wants to invest further in renewable energy to replace the use of fossil fuels. “We fully support the concept of deployment of renewable energy, and we believe it’s a key driver in the energy transition process,” he said.

Currently, Suriname’s installed capacity of power generation is 504 MW from all sources, with 61% coming from fossil fuels, 38% from hydroelectric power, and about 1% from other renewables, according to Abiamofo. He said the country is in the process of assessing its potential for wind energy, with the assistance of the IDB, and is studying the possibility of generating energy from rice husks.

As to the upcoming development of the oil and gas sector, Abiamofo stressed that the government wants to ensure that Suriname’s people benefit from these resources. Most of the goods and services should be delivered by Surinamese companies and most of the workforce should be Surinamese, he said, adding that the educational system needs to be aligned with the needs of the workforce.

David Abiamofo, Minister of Natural Resources of Suriname, during the Fifth ECPA Ministerial Meeting, Panama 2022 | Credit/source: Panama Presidency

Abiamofo said government policy includes “the creation of a sovereign wealth fund and the development of local content as sustainable support for local entrepreneurship and human development.”

Noting the global concern about climate change, which he called “one of the greatest challenges of our time,” Abiamofo said Suriname will seek ways to mitigate the impacts of petroleum production and will “demand that oil and gas companies have to measure and monitor and report their greenhouse gas emissions.” Clear standards are already in place for the national oil company, Staatsolie N.V., and will also apply to other companies, in order to “rigidly monitor” Suriname’s carbon-negative status, he said.

View Map

View Map