“Brazil is at an excellent moment for the growth and use of renewable energy,” said Fábio Rosa, who founded and heads IDEAAS, a Porto Alegre-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) that promotes renewable energy and sustainable development in rural and isolated areas. He also chairs a national network of civil society organizations that support renewable energy, called RENOVE.

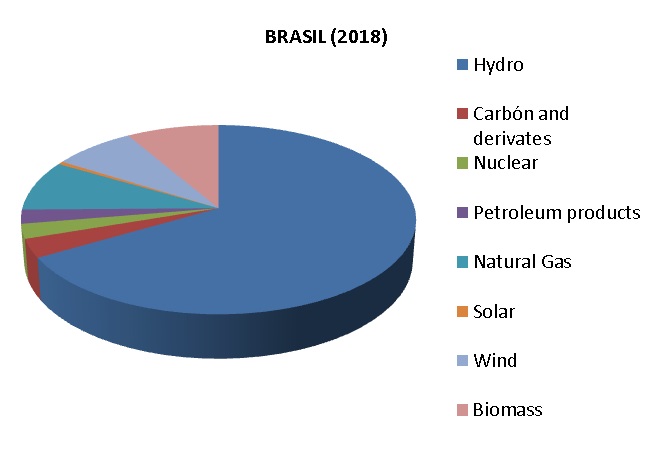

Wind energy, in particular, has seen dramatic growth in the past decade; it accounted for 8% of the electricity Brazil generated in 2018, official figures show. That’s up from 0.4% in 2010, according to the state-owned Energy Research Company (EPE for its Portuguese acronym), which compiles energy data for the Ministry of Mines and Energy and other agencies.

In that same period, electricity generation from hydropower decreased, from 79% in 2010 to about 65% in 2018.

Fábio Rosa attributes the boom in wind energy to a solid legislative and regulatory foundation—beginning with a law passed in 2002 (Law 10.438) and a program it created called PROINFA, which established incentives to stimulate investment in wind, biomass, and small-scale hydro.

“Everything that has happened in our history of progress and large-scale use of wind energy is related to this law, to this program,” Rosa said in an interview. The program, he added, ensured stability for investors and spurred the gradual development of the wind industry in Brazil.

That point was echoed by José Henrique Gabetta, an energy consultant in Minas Gerais state who runs another Brazilian NGO that promotes renewable energy, Instituto Consciência Limpa. Under PROINFA, Gabetta said, the government made a commitment to purchase a large block of wind energy at a price that attracted international companies and led to capacity being developed within Brazil.

“It’s a great example of how to do things right,” Gabetta said, noting that companies specialized in every aspect of wind technology now operate in the country.

In 2012, another measure—Regulatory Resolution 482, issued by the National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL)—provided incentives for distributed generation on a small scale (“micro,” up to 75 kW, and “mini,” up to 1 MW).

The rules established a net metering system to allow customers that generate their own electricity to get credit from electric utilities for any excess power they feed into the grid. This applies whether the electricity is generated on a company’s premises or elsewhere, say on a solar farm outside the city where the company is located.

“Once again, a high-quality regulatory foundation opens a new door, and that’s where major progress begins in terms of the scale of solar photovoltaic energy in Brazil,” Rosa explained.

Solar power makes up the largest portion of distributed energy, though it still represents a blip on the energy map; according to EPE figures, solar accounted for just 0.6% of the electricity generated in 2018. But solar production grew by more than 300% from 2017 to 2018.

However, Gabetta expects that pace to slow down, due to proposed regulatory changes set to take effect in mid-2020. Under the proposed rules, which he described as a “setback,” the amount of credit for excess power fed into the grid would go down; instead of getting a 100% credit for every kilowatt, companies producing their own energy would get a 72% credit. That would significantly increase the payback period for investments in distributed generation, he said.

The proposed rule changes are a result of pressure from utilities, according to Gabetta, but he and other advocates of distributed generation are trying to make the case that such pressure is unwarranted at this stage. Distributed generation currently makes up less than 1% of all electricity consumption in Brazil, he said, and poses no threat to the profitability of electricity distribution companies.

Plus, Gabetta argued, it just makes economic sense to encourage distributed generation. Although Brazil’s current economic growth rate is anemic, once growth picks up, the country will need all the energy it can get, he said.

Gabetta believes the next wave of renewable energy growth in Brazil will come from biomass, which includes different forms of production using plant or animal material. In some cases, biomass is burned to generate energy, as with bagasse, a residue from sugar production; in other cases, energy in the form of biogas can be captured during the decomposition of organic matter, such as cow manure.

With its massive agriculture and livestock industries—and the environmental challenges involved in disposing of the associated waste—Brazil has the capacity to harness a significant amount of energy from this renewable source, according to Gabetta. Some states are starting to adopt incentives to encourage biogas development, he said.

In separate interviews, both Gabetta and Rosa expressed some discouragement about what they consider short-sightedness in their own country and beyond, when governments turn to unsustainable or potentially dangerous forms of energy rather than readily available clean solutions.

In Brazil, they mentioned the current government’s announced interest in building several nuclear power plants, as well as past governments’ decisions to undertake mega-hydroelectric projects with major social and environmental impacts; Belo Monte, one of the largest dams in the world, is the latest such undertaking. “There’s no need to flood the Amazon region,” Gabetta said.

Examples abound worldwide too, Rosa said—take Russia’s recent introduction of a floating nuclear power station in the Arctic. It’s not about ideologies of the left or right but about “the foolishness of humanity,” Rosa said.

Still, he is optimistic about the future of renewables—particularly solar and wind, where Brazil and other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean enjoy enormous natural advantages. He noted that when it comes to the intensity of solar radiation (insolation, as it is known), the worst conditions seen in Brazil far outperform the best conditions in Germany, which is among the world’s leading solar energy producers.

The NGO Rosa leads, the Instituto para o Desenvolvimento de Energias Alternativas e da Auto Sustentabilidade, works in southern and northeastern Brazil, as well as internationally, to promote clean energy. One project brought electricity—in the form of 420 stand-alone solar home systems—to some 1,000 people who work for a sustainable tree-farming operation in a remote part of southern Brazil.

The falling costs of solar and wind power mean the energy transition is here to stay, according to Rosa. “It’s not possible to stop because it’s competitive,” he added.

And while the intermittent nature of these sources has long been a limitation, Rosa said, that is on the verge of being solved through advances in battery storage. Just as petroleum and coal are types of stored energy, as is a dam’s reservoir, a “new revolution” in technology will soon make wind and solar energy just as reliable.

“This is happening, and it will happen,” Rosa said. “Whether governments like it or not, this is an inevitable new world.”

View Map

View Map