Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has long denounced the energy reforms the previous administration put in place beginning in 2013, says the new law will promote “energy sovereignty” and strengthen the state-owned Federal Electricity Commission (CFE).

But critics argue that this reform, which amends the 2014 Electricity Industry Law, will make Mexico less competitive, deter investment, and hurt the environment.

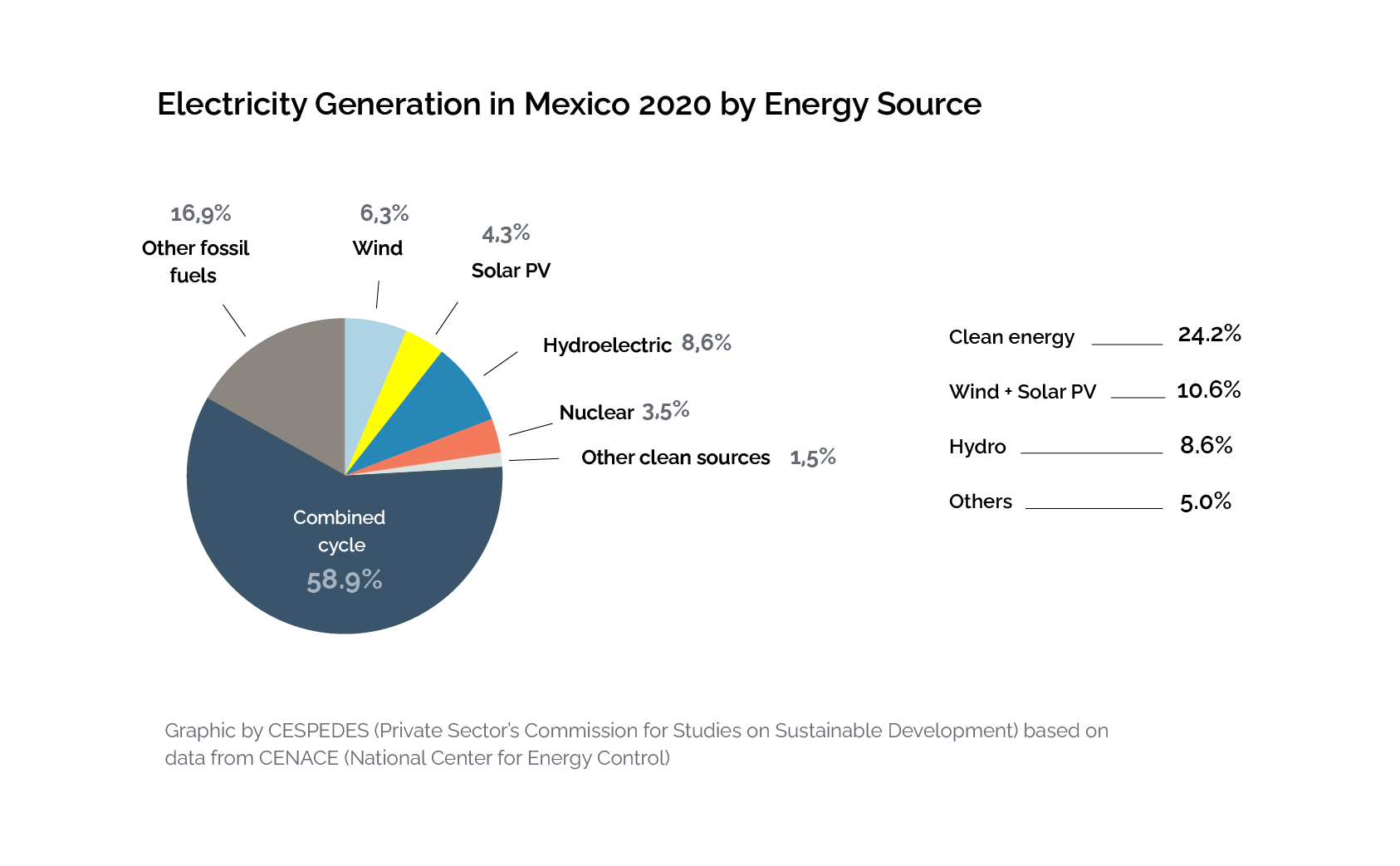

One provision that has prompted fierce criticism is a change in the order by which generating plants feed electricity into the national grid, which is owned and operated by CFE. Under the 2014 law, which remains in effect for now, dispatch priority is based on price; in other words, a plant that produces electricity at a lower cost is further ahead in line than a less efficient competitor. That has given an edge to wind and solar power, and investment in these types of renewable energy has exploded in recent years.

The amended law would give priority to state-owned power generation, regardless of price. That means, for example, that power from a CFE-owned plant that burns fuel oil would be favored over wind or solar power generated by private companies.

During a two-day forum last month on “Electricity for the Future of Mexico,” sponsored by Mexico’s Business Coordinating Council (CCE), speaker after speaker said that this made no sense from an economic, technical, legal, or environmental standpoint.

“There is no way, no angle by which we can see that this will improve competitiveness in the country,” said Valeria Moy, General Director of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (IMCO), a non-profit, non-partisan research center.

Montserrat Ramiro, a former Commissioner of Mexico’s Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), questioned whether prioritizing inefficient power generation was the best use of public resources. “What is absolutely indisputable is that with this structure being presented, the costs are going to be higher,” she said.

The impacts on public health and the environment will also be extensive, several participants pointed out. José Ramón Ardavín, who leads the Private Sector’s Commission for Studies on Sustainable Development (CESPEDES), said Mexico must significantly cut its carbon emissions in the electricity sector—not increase them—if it has any chance of meeting its goals under the Paris Agreement.

The new law goes against the worldwide trend toward an accelerated energy transition and more electrification and digitalization, noted Lourdes Melgar, a leading energy official in the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto and one of the architects of its energy reforms. And even though the amended law is intended to help CFE, it will end up undermining the company’s autonomy by forcing it to buy fuel oil from the state-owned oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), Melgar said.

“As long as the electric system is being defined by political and not technical issues, Mexico will lose the future,” she said.

The Federal Electricity Commission is one of Mexico’s largest publicly owned companies. Created in 1937 under the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas—who the following year would nationalize the oil industry and create Pemex—it is the country’s leading generator of electricity and has a monopoly on transmission and distribution. The company has more than 94,000 employees, according to its website.

CFE generates power from a wide array of sources, including hydroelectric, wind, solar, coal, nuclear, geothermal, oil, and gas. In addition to the electricity that it produces, it purchases power from private generation companies for distribution through the grid.

The new dispatch system would give priority to CFE-owned generation, starting with hydro, followed by its thermal plants. Next come privately owned wind and solar generation, with private combined cycle plants last in line.

“As CFE’s hydroelectric plants cannot satisfy the country’s electricity demand, the main beneficiaries would be CFE’s technologically obsolete, polluting plants that take second place on the dispatch list,” wrote Oscar Ocampo, Coordinator for Energy at the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, in a paper published by the Wilson Center.

This arrangement benefits not only CFE but also Pemex, which would be able sell more of its high-sulfur fuel oil to supply CFE thermal plants, according to Fernando Rodríguez-Cortina, a Mexican lawyer who works in the Houston office of the law firm King & Spalding.

“That fuel cannot be exported,” he said in an interview with the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA). “Nobody’s going to buy it because it’s so dirty that it doesn’t comply with the international standards.”

In a recent podcast, he and Roberto Aguirre Luzi, a partner in the firm’s international arbitration practice, talked about some of the potential consequences of the new law, which they expect will eventually give rise to numerous international claims. They noted that Mexico has entered into bilateral investment treaties—agreements designed to protect investors—with some 40 jurisdictions. The current situation creates “uncertainty over more uncertainty, and a lot of warnings for investors that have either sunk millions of dollars in the power sector or were thinking about it,” Aguirre Luzi said.

In an interview, he said that the amended law would discriminate against private companies that invested in the Mexican power sector based on clear rules establishing open, non-discriminatory access to the grid.

“You were under the exact same circumstances as the state-owned generation, and now you’re going to be dispatched after that, when you invested based on the assumption, on the legal framework approved by the government, that allowed you to be dispatched based on your marginal cost,” Aguirre Luzi explained.

The changes will not only increase pollution and disincentivize investment in efficient and cleaner energy, he said, but will also increase the system cost of producing electricity.

Increased cost was a frequent topic raised during the recent forum. Currently, natural gas-fired combined cycle power plants are the biggest source of electricity in Mexico. If they have to take a back seat to less efficient thermal plants, CFE could end up paying between (US) $2 billion and $3 billion more for electricity per year, according to a computer modeling study done for the Business Coordinating Council.

The Mexican president has promised that residential consumers will not see their electricity bills go up, but several energy experts said that people will end up paying more, if only indirectly. One way, they said, would be through higher taxes, if energy subsidies need to be increased; another way would be through overall higher prices on goods and services, as businesses that have to pay more for electricity pass along their costs to consumers.

Carlos Salazar, who heads the Business Coordinating Council, said the electric power that private companies produce in Mexico and sell to CFE for distribution costs 26% less, on average, than that produced by the state-owned utility itself. He stressed that he wasn’t implying that CFE is poorly managed but simply pointing out that the private sector plants tend to use newer technology that is more innovative and efficient.

“We all want electricity to reach us at lower prices, but this will be possible only if and when we have lower costs to produce it,” he said. Salazar noted that his organization had tried earlier this year to engage the legislature on the electricity bill, focusing strictly on technical and economic issues, but that it was denied an opportunity for dialogue.

As it happened, the Senate gave final approval to the legislation in the early morning hours of March 3, just hours before the start of the business forum.

Once the law was published in the Official Gazette, it encountered “an avalanche of legal challenges,” as Ocampo described it. A court has suspended implementation of the law, but “the outcome of these legal battles is still uncertain and will likely be defined by a ruling of the Supreme Court,” he wrote.

During the forum, several participants talked about the likely legal challenges ahead, on both national and international fronts. If the new takes effect, they argued, it would fly in the face of other laws in Mexico and violate several constitutional provisions, as well as breach international treaties such as the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Participants also talked about how they could more effectively make their arguments heard by the public. Managing Editor Luis Miguel González of the Mexican business newspaper El Economista said it’s important to convey a strong, clear message about the importance of having a more competitive, more open, and cleaner power sector.

One challenge, he said, is that the business community tends to talk about energy reform in complicated, technical terms, whereas the government has advanced a broad narrative involving sovereignty and nationalism.

“When a discussion pits the complex against the simple, the simple is going to win,” González said. He added that López Obrador has been adept at finding the right moments to highlight his priorities. For example, when Mexico faced power outages as a result of the energy crisis in Texas, the president used that opportunity to talk about the need for the country to be energy-independent.

At the same time, López Obrador has often singled out foreign energy companies for criticism, claiming that they have benefited unfairly from the reforms of recent years and accusing some of them of corruption.

A few weeks after the enactment of the new Electricity Industry Law, the president introduced an initiative to amend the Hydrocarbons Law. In a letter introducing the proposed reforms to Congress, he said, “It is imperative to strengthen the productive companies of the Mexican state as guarantors of energy security and sovereignty and a lever of national development, to trigger a multiplier effect in the private sector.”

For her part, Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, a close ally of López Obrador and a high-profile proponent of renewable energy, recently voiced her support for the amended Electricity Industry Law. Speaking at an event to commemorate the anniversary of the 1938 nationalization of the oil industry, she said the law would benefit the country and help strengthen sustainability and sovereignty.

“The interests of the nation will be placed above private interests, guided by the interest of the people and their well-being,” she said.

Opponents of the new law, however, believe that the message of well-being belongs to their side, and recognize that they need to get better at making that argument. This is not about winning over “technical folks,” Roberto Newell, former Director General of IMCO, said at the forum, but about “convincing the people.”

While the change to the dispatch order has garnered the most attention in discussions about Mexico’s amended Electricity Industry Law, other parts of the law are also noteworthy. In a paper published by the Wilson Center, Oscar Ocampo of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness notes that the law would also:

View Map

View Map