Energy efficiency is one of those topics that everyone can agree should be a priority. “The best energy is the energy that is not used,” said Sergio Segura Calderón, Director of International Cooperation at Mexico’s National Commission for the Efficient Use of Energy (CONUEE). Energy efficiency tends to be a good investment, he added, one that makes companies and economies more productive and competitive and typically pays for itself in a relatively short period of time.

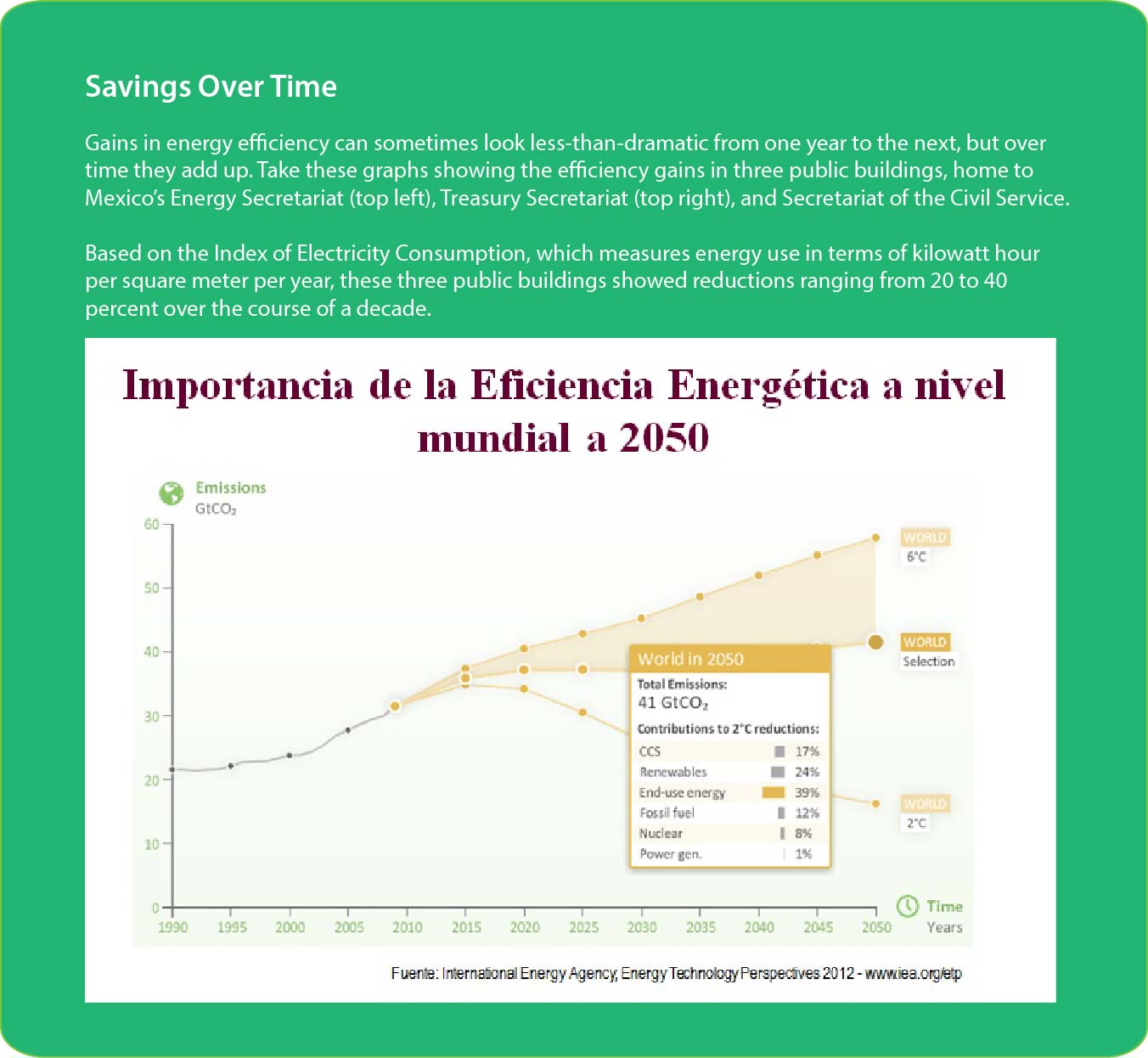

The International Energy Agency (IEA) calls energy efficiency “the first fuel,” noting in a recent report that this is “the one energy resource that all countries possess in abundance.” The United Nations, through Sustainable Development Goal 7, calls for doubling the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency by 2050.

So why is the idea of energy efficiency sometimes hard to sell?

One problem, Segura said in a phone interview, is that it is “not as sexy” as a new wind farm or solar power facility, because it is largely invisible. It’s as if somebody said, “Look at the beautiful electric plant that wasn’t built,” as Segura put it with a laugh.

Despite this image problem—or, rather, invisibility problem—energy efficiency has a critical role to play in meeting the world’s climate goals. “Although end-use energy efficiency alone is not sufficient to meet the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement, it can deliver 35% of the cumulative CO2 savings required by 2050,” the IEA states in a report published this year, Perspectives for the Energy Transition: The Role of Energy Efficiency.

This potential to make a difference helps to explain why energy efficiency is one of the central pillars of the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA), and why Mexico wants to help other countries in the region benefit from its experience. CONUEE has proposed providing technical cooperation in this area through ECPA. While details have yet to be worked out, Segura said, the first step will likely be a series of webinars, which could be followed by technical missions, depending on available funding.

CONUEE’s Energy Efficiency Program for the Federal Public Administration focuses on three areas: federal government buildings, vehicle fleets, and state-run industrial facilities. The first of these has the longest track record, dating back to the 1990s.

It all started with a study to identify potential savings in 100 public buildings across the country, according to Hebert León Sánchez, CONUEE’s Director of Energy Efficiency for Buildings. León, who has been involved in this effort practically from the start, said in an interview that his agency wanted to come up with some baseline data for different parts of the country with different climates, so it began to contact other federal government agencies to ask whether they would share information about energy use in their buildings.

That study had just been completed, in the late 1990s, when the federal government announced a comprehensive austerity program, calling for all agencies to find ways to cut costs. Based on the study, the Energy Secretariat was able to propose an internet-based program designed to improve energy efficiency in public buildings and achieve significant cost savings.

The program has been operating ever since, working to wring more energy savings every year out of buildings owned by the federal government. In 2016, the most recent year for which detailed figures are available, 218 federal offices and agencies with 2,344 properties and 7,326 buildings participated in the program. (Many properties, whether university campuses or office complexes, have multiple structures.) The average energy use per square meter in these buildings dropped by 1.2 percent in 2016, according to CONUEE figures.

The program is mandatory for federal buildings with more than 1,000 square meters of floor space, though CONUEE has no way of imposing sanctions for noncompliance, and it is unclear how many federal buildings that should be participating are not, according to León. That doesn’t mean there is no oversight, he said. Each agency that participates is required to form an internal committee to monitor energy savings, and one member of that committee must be the government auditor assigned to track the agency’s performance in a range of areas, including energy efficiency.

“That helps us a lot,” León said, adding that government agencies tend not to want to catch the auditor’s attention by failing to comply with regulations or guidelines.

The properties that participate in the program are required to regularly report their energy use and meet certain benchmarks every year. While the system is not perfect, one sign of its success is its sheer longevity, León said, noting that the government has steadily made efficiency gains for nearly two decades.

Funding for energy efficiency remains a chronic problem. León said that at this point, most government agencies have implemented any best practices that require little or no investment, such as changing indoor lighting or conducting internal campaigns to encourage energy efficiency. When it comes to making larger investments, though—say a new air conditioning system—they tend to wait until the old equipment breaks down and then simply replace it, without doing any research or planning.

In the last few years, CONUEE has been working with agencies to implement energy management systems so they can get a more complete picture of “how much energy they use, where they use it, and how they use it, so that they can then take the necessary measures,” León said. The government is also implementing a pilot program, with a loan from the Inter-American Development Bank, to test the potential return on investment of replacing major heating and cooling systems in selected federal buildings.

With global attention on climate change and the Paris Agreement, León sees a growing awareness these days of the need not only to cut costs but to save energy—sometimes to an extreme. “You’ll walk into offices and they’ll be dark,” he said, adding that in such cases the building managers might have lowered the wattage so much that they’re in violation of other regulations that require a minimum amount of lighting in offices. “That’s not saving energy, because then you’re affecting people’s health,” he said.

View Map

View Map