“Activism is not only in the streets,” said María Alejandra Téllez, co-founder of a nongovernmental organization (NGO) in Colombia called ClimaLab. Now 28, she’s been working since 2017 to raise climate awareness in schools and develop projects to help communities that are feeling the effects of a changing climate.

The climate crisis is so urgent that it requires action on every front, she and several other young adults in the region said in recent interviews with the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA). Téllez, a lawyer who now runs ClimaLab full-time, sees her work as complementing the more visible activism of demonstrators or social media influencers.

“Taken together, all of us are generating a major impact in Colombia, and that’s the power of youth,” she said.

ClimaLab founders: Maria Alejandra Téllez, Andrés Urrego and Jhoanna Cifuentes.

In Brazil, Cassia Moraes is one of four young women who founded Youth Climate Leaders (YCL), an organization that aims to educate young people about climate change and open doors for careers that can make a difference.

“What is the most effective thing that you can do for the climate crisis? Make it your full-time or part-time job,” Moraes said. YCL teaches young people about climate change through a series of courses—offered only in Portuguese so far—and provides scholarships to ensure that the classes include people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The challenges related to climate change will create massive numbers of new jobs and change many others, Moraes said. Some may find new opportunities in renewable energy industries, for example, while others may end up bringing a climate perspective to some other type of career, whether in the law or journalism or agriculture or the restaurant business.

Cassia Moraes (in red) with members of Youth Climate Leaders

“There’s not sector that will not be affected somehow by climate change,” said Moraes, who is 31. She believes that the potential for young people to be able to pay their bills while furthering a good cause can be a real drawing card, especially at a time when unemployment rates are high and many are struggling financially. YCL has entered into a partnership agreement with the state of São Paulo to develop a virtual training course on climate to be offered by the state’s technical schools.

In Panama, Juan Carlos Monterrey helped start an intensive week-long Climate Leadership Academy for Youth in 2018, when he was working for the Ministry of the Environment. In selecting the first group of participants—there have now been three editions of the training program—the organizers looked for promising young leaders, whether they had been working on environmental issues or not.

“In order to turn this crisis around, we actually need people in every field, from every walk of life, to start talking climate,” Monterrey said.

The first 30 young people to go through that climate training went on to start Jóvenes y Cambio Climático (Young People and Climate)—the first civil society organization in the country focused solely on climate change, according to Beatriz Reyes, who has led the group for the past two years.

Reyes, 25, believes awareness about climate change is growing, but she would like to see more people feel the same urgency she does about the need to address the problem. Her group has organized local activities, such as a Climathon event in October to highlight ways to make Panama City more pedestrian-friendly. Under a United Nations initiative called Local Conferences of Youth, the group also adopted a declaration to provide input to the UN climate conference known as COP26—held last month in Glasgow, Scotland.

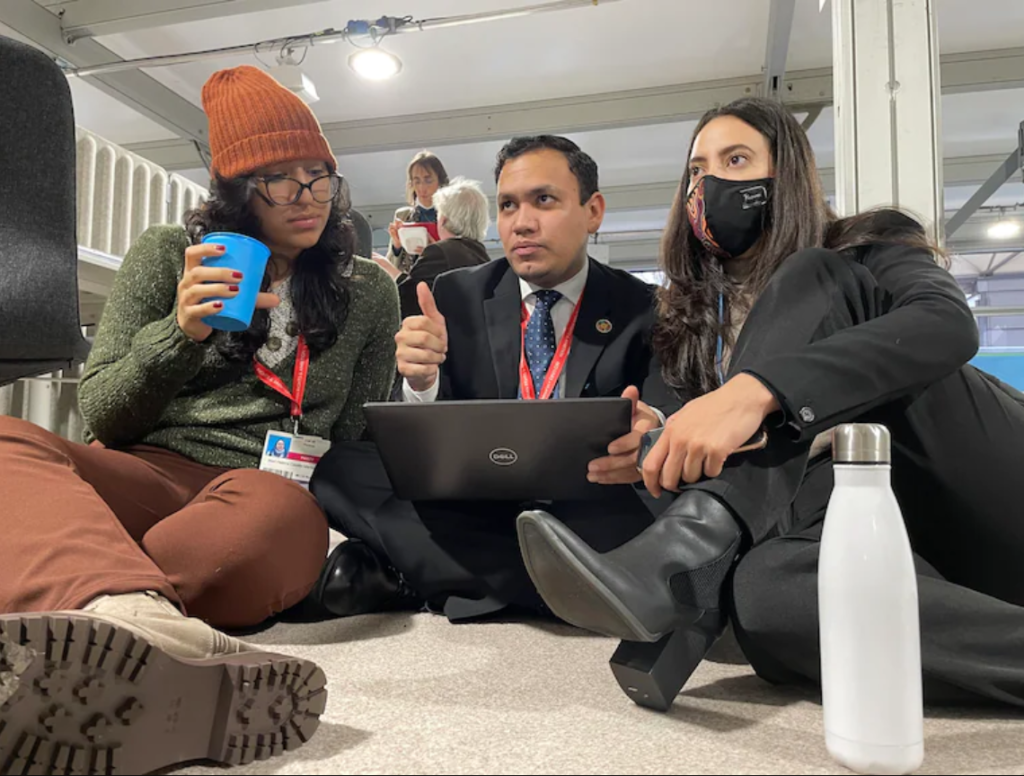

A selfie moment at COP26.: Juan Carlos Monterrey, Mari Castillo and Nicole Francisco.

Panama’s official delegation of negotiators at COP26 was the youngest among the nearly 200 countries at the conference, according to Monterrey, who led the negotiating team; the average age of the lead Panamanian negotiators was 26.

Monterrey himself is 29 now, but his experience as a climate negotiator for his country dates back to when he was 22. He landed an even more prominent spot in the public eye recently, when he was tapped to do a symbolic reading of the Declaration of Independence at the bicentennial celebration of Panama’s independence from Spain, on November 28. When he’s not representing his country, he works in a technical assistance position for the World Bank in Panama.

More countries should follow Panama’s lead and give young people decision-making power on climate change issues, Monterrey said. “You cannot negotiate the future of current and future generations if you are not putting people from those generations at the table to negotiate their own future.”

Of course, most of the younger faces in the news in Glasgow were not in the negotiating rooms but outside, among the tens of thousands of activists who made their voices heard in the streets. One of them was Francisco Vera of Colombia, who already has a huge following as an environmental activist even though he is just 12.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg at a protest in the lead-up to COP26.

Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, whose name is now practically synonymous with climate action, was 15 when she helped launch what became a worldwide student movement known as Fridays for Future. In advance of COP26, she famously dismissed world leaders’ promises on climate change as “blah, blah, blah”—a phrase that found its way into U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s opening speech. (The promises of Paris, he said, “will be nothing but ‘blah, blah, blah,’ to coin a phrase, and the anger and the impatience of the world will be uncontainable unless we make this COP26 in Glasgow the moment when we get real about climate change.”)

Former U.S. President Barack Obama, speaking in Glasgow, noted that young leaders around the globe are hard at work pressing for change. “A lot of people now know about Greta, but the world is full of Gretas,” said Obama, who also singled out Juan Carlos Monterrey (an alumnus of the Obama Foundation Scholars program) for his leadership.

Obama urged the young and the young at heart to keep the pressure on governments and businesses to take climate change seriously, and to channel their anger and frustration to produce real results. “Gird yourself for a marathon, not a sprint, for solving a problem this big, this complex, and this important has never happened all at once,” he said.

Barack Obama urged young people to prepare for “a marathon, not a sprint” on climate issues.

The young people who spoke to ECPA shared some other words of advice for their peers who want to do something about climate change but don’t know where to start:

Know your stuff. Taking to the streets can be seductive, but it can be a superficial exercise if people don’t take the time to study the climate problem, learn the facts, and get a sense of how to go about solving a complicated issue, Moraes said. “If it was simple, we would have solved it,” she added.

Find your niche. “I think that every young person needs to do some soul-searching and try to identify what are their skills and where in this massive spectrum their skills will be used better,” Monterrey said. For some, that may mean participating in marches or knocking on doors; others may go into more technical or academic fields, or the civil service—or express their concerns through art or poetry.

“Youth are finding creative ways to make their voices heard, and that’s what keeps me optimistic,” Monterrey said.

Dive into policy. In Colombia, ClimaLab and other youth organizations made recommendations to the government as part of the process undertaken to update the country’s climate commitments (known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs). One of their recommendations: make climate change and sustainable development an integral part of the required curriculum in schools.

“Young people are often counted out because we don’t have enough experience,” Téllez said. However, she added, she and her peers have a lot to say and should make themselves heard when it comes to public policy.

Insist on a seat at the table. “If there aren’t spaces for young people, you have to create them,” Reyes said. When she and her peers found that they were being left out of some official events related to climate change, they started hosting events themselves and inviting authorities to participate in panel discussions.

Some government agencies in Panama, such as the Energy Secretariat, believe strongly in youth participation, while others need nudging, Reyes said. When governments are developing strategies and policies, she added, they should include youth throughout the process. And it’s important for young people to show that they are knowledgeable about the subject and understand how decisions are made.

Consider politics. Monterrey said he personally has no plans to run for public office, but he encourages young people to become involved in the political process and in government. “In the end, governments are the only entities that actually have the power, the capacity, and the money to set in motion transformations that we need to stop this crisis.”

Juan Carlos Monterrey speaking at COP26.

Juan Carlos Monterrey, who led Panama’s young negotiating team at COP26 in Glasgow, made it clear in a final statement to the conference that his country was far from happy with the end result. Some of the decisions made were drafted by the largest emitters for their own benefit, he said, while the needs and contributions of rainforest countries like Panama were not sufficiently considered.

“We had the opportunity here in Glasgow to pave the way to keep fossil fuels in the ground, but the approved package fails to keep them in the ground,” he told the conference. “Shame on us.”

Still, he noted, the overall text did represent a step forward in raising climate ambition—“not a perfect step, but a step in the right direction nonetheless.” (Read the Glasgow Climate Pact here.)

In a recent interview, Monterrey talked about some of his frustrations with the process. In some cases, he said, negotiators seemed to be more interested in currying favor with the larger countries rather than aggressively defending their own nations’ interests.

The Panamanian delegation drew a lot of media attention at COP26 because of its relative youth. During one event at which only official country representatives were allowed to speak, the delegation agreed to deliver a statement on behalf of climate activists who had been unable to make themselves heard.

Panama’s deputy lead negotiator, 25-year-old Mari Castillo, read the statement, which admonished national and corporate leaders for falling short on their climate obligations, during “a plenary event defined by congratulations and politesse,” the Washington Post reported. “We look to you as global leaders, yet your actions are failing us,” she read.

While the diplomatic process can be a bit frustrating at times, Monterrey said in the interview, it’s important to keep trying.

“Progress is not perfect,” he said. “Sometimes you go three steps forward and you go two steps backwards, but you make that step forward in the overall balance. Incremental progress is the only way that progress has ever happened in history.”

View Map

View Map