In early 1999, less than three months after Hurricane Mitch had plowed through his fields, wiping out the corn, potatoes, and other crops he had planted, Israel Vaíl headed for the United States to take his chances as an undocumented immigrant. Now back in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, he looks back on that decision as his only option at the time. “The hurricane destroyed my crops and I couldn’t pay my debts,” he explained.

In early 1999, less than three months after Hurricane Mitch had plowed through his fields, wiping out the corn, potatoes, and other crops he had planted, Israel Vaíl headed for the United States to take his chances as an undocumented immigrant. Now back in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, he looks back on that decision as his only option at the time. “The hurricane destroyed my crops and I couldn’t pay my debts,” he explained.To some extent, climate-driven migration affects all countries, large and small, rich and poor. In the United States, Hurricane Katrina displaced hundreds of thousands of people in 2005, with New Orleans losing more than half its population for a time. While the city has been growing again in recent years, it’s still considerably smaller than it was before.

The Central American and Caribbean regions are especially vulnerable to violent storms. In a 2014 report—Human Rights of Migrants and Other Persons in the Context of Human Mobility in Mexico—the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights looked at some of the causes for migration to and through Mexico. It found that natural disasters in Central America and the Caribbean “are now figuring more prominently among the hardship factors that cause many in the region to migrate.” In addition to hurricanes, torrential rains, and flooding, the report cited such factors as the increasing intensity of the dry seasons, soil degradation, and sea-level rise.

The Global Climate Risk Index 2016 lists the 10 countries in the world most affected by climate effects over a 10-year period (1995-2014), and four of them are in Central America or the Caribbean: Honduras (#1), Haiti (#3), Nicaragua (#4), and Guatemala (#10). The index, produced by a nongovernmental organization called Germanwatch, primarily reflects the direct impacts of extreme weather events. It notes that even though monetary losses tend to be greater in richer countries, “poorer, developing countries are hit much harder.”

Sometimes, when a sudden catastrophe strikes, migration is all but inevitable. This was the case for more than 800 residents of Petite Savanne, Dominica, who had to be permanently evacuated after flooding and landslides brought by Tropical Storm Erika devastated their town in August 2015. (The government of Dominica is in the process of planning a new community that will be built for the evacuees, according to a report earlier this year by Caribbean News Now.)

Other effects of climate change evolve more slowly. In the Andes, for example, glaciers are a critical source of fresh water, but with rising global temperatures they are melting at unprecedented rates. In Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, smaller glaciers at lower altitudes (around 5,000 meters) are likely to disappear completely within a generation, according to Walter Vergara, a climate specialist at the World Resources Institute.

“This is terrifying, because there are many glaciers that are below 5,000 meters,” said Vergara, who coauthored a study on the subject when he worked for the World Bank. In addition to receding glaciers, higher temperatures also contribute to the drying of high-mountain wetland ecosystems known as páramos, which store and release water over time. All of this means that less water will be available in the future for agriculture, energy production, and other uses.

“Eventually, people who live in the high-altitude basins are going to have to adapt or migrate,” Vergara said in an interview.

“Eventually, people who live in the high-altitude basins are going to have to adapt or migrate,” Vergara said in an interview.

Another example of a slow-motion climate event is coral bleaching, which is linked to rising sea surface temperatures. This problem not only has an impact on tourism, by dimming the bright colors that draw snorkelers and divers; it also threatens fishing, as coral reefs support fish colonies. In some communities in the Caribbean, many people who depend on fishing for their livelihood could end up having to relocate, Vergara said.

To be sure, long-term adaptation measures are underway to address both of these situations. In the case of the coral reefs, scientists are doing genetic studies to identify corals that are more resistant to higher temperatures—a process Vergara described as “a race against time.” Andean countries, meanwhile, are looking at measures such as creating high-altitude man-made reservoirs and introducing drought-resistant plants.

No matter what the particular climate risk, Vergara said, countries and communities must step up their efforts to visualize long-term impacts and engage in serious strategic planning. In the meantime, he added, the region needs to make every effort possible to eliminate fossil fuel emissions. “It’s something we can do now,” he said.

Building Awareness

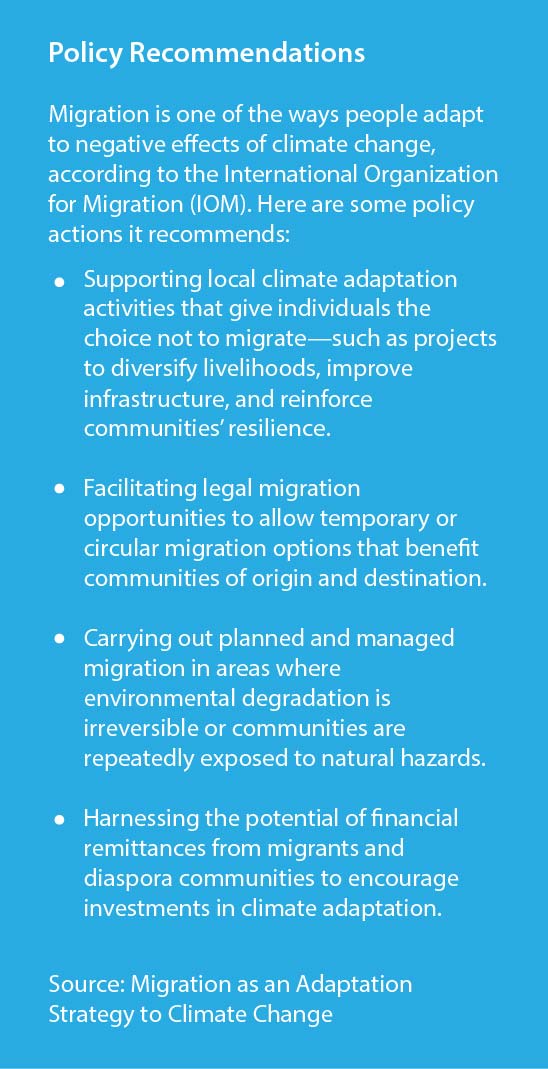

On a global scale, the issue of migration and population displacement is becoming more widely discussed in the context of climate change. The Paris Agreement adopted in December 2015 includes migrants among the groups whose rights must be protected, and refers to the need for “integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change.”

Speaking in Paris during the climate talks, the Director General of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), Ambassador William Lacy Swing, said that including the issue in the agreement would help raise the visibility of “climate migration” as one of the many factors driving “unprecedented human mobility.”

“I don’t think that, generally speaking, our governments, particularly our parliaments, are well enough aware of what is happening and why they have a responsibility to address this in both monetary and policy terms,” he said.

Of course, migration is often a complex phenomenon with multiple causes. Ambassador Nestor Mendez, Assistant Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), noted that non-environmental factors often come into play after a disaster and contribute to a decision to migrate.

“If you have a very poor community that is already suffering from poverty, from poor governance, from the inability to access certain basic services, these people are more vulnerable to moving if they’re struck by a hurricane or a drought or a flood because the infrastructure is not in place to give them some of the basic protections that would enable them to resist these kinds of natural disasters and remain at home,” he said in an interview. With all the work to be done to address the causes of climate change, “we also have to look at ensuring that the vulnerabilities of our communities are reduced,” he added.

The OAS can help bring attention to the issue and encourage countries to establish protocols to deal with climate-induced migration, Ambassador Mendez said. “It needs an integral approach, because to reduce the vulnerabilities to climate change requires a lot of work in many areas”—from poverty alleviation and social safety nets to smart building codes that prevent construction in low-lying coastal areas. Although national governments typically handle responses to natural disasters, he said, it’s also important to work with local governments since much of the implementation happens at that level.

“I would like to encourage everybody who has a role in community leadership, in local government leadership, in central government, to help in creating an awareness of how the changes in climate will be impacting our people going into the future and how we need to prepare for it, because it’s a reality,” the Assistant Secretary General said.

View Map

View Map