Brazil and Colombia both have potential offshore wind projects in the works. On March 6, the Brazilian state-run oil company Petrobras and the Norwegian energy company Equinor announced that they had signed a letter of intent to assess the technical, economic, and environmental feasibility of seven wind power generation projects off the Brazilian coast.

The projects have the potential to generate up to 14.5 gigawatts of power and could help advance Brazil’s energy transition, the companies said in a joint announcement.

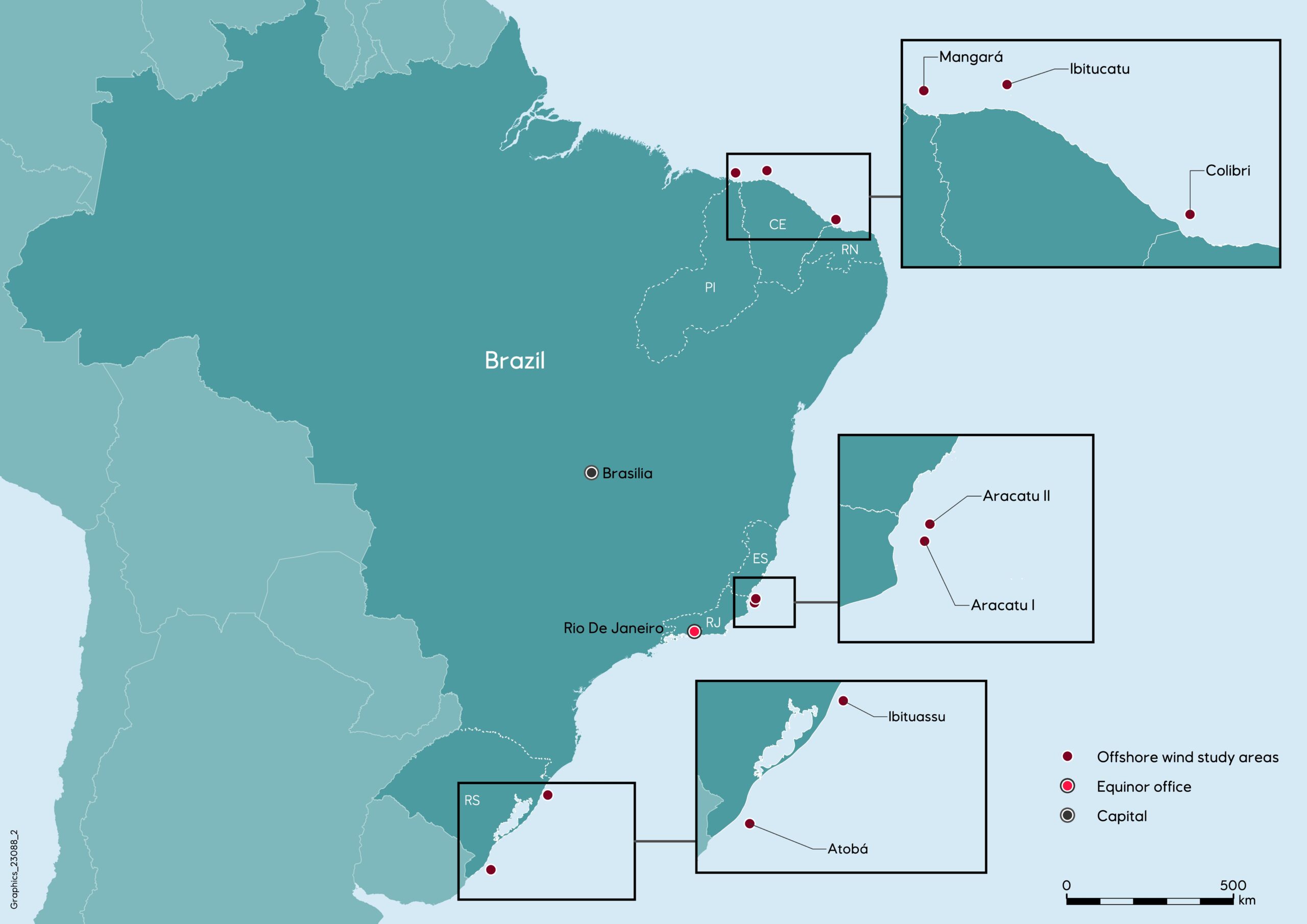

Petrobras and Equinor have had a partnership in place since 2018 to assess two potential wind farms on the coastal border between the states of Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo. The new agreement, effective until 2028, expands that partnership to include the assessment of five other offshore locations: three in northeast Brazil and two in the southeast.

Credit: Equinor

In Colombia, meanwhile, the city of Barranquilla is planning an offshore wind pilot project it says could generate between 250 and 500 megawatts to be used in the production of green hydrogen.

The Mayor’s Office announced on March 1 that it had submitted plans to the Ministry of Mines and Energy for the city project, which it said would be carried out by the Colombian public-private company K-YENA with the support of Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, as well as the participation of the national oil company Ecopetrol.

Brazil and Colombia have taken the lead in the region in developing roadmaps and regulatory frameworks for offshore wind, according to several panelists who participated in an event hosted last September by the Inter-American Dialogue.

But interest in this sector is widespread. Mark Leybourne, co-leader of the World Bank Group’s Offshore Wind Development Program, said his institution had provided support on offshore wind to eight countries in the region, including Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Uruguay.

The Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based think tank, hosted a webinar last year titled “Offshore Wind Energy in LAC – Gauging Speed and Direction.” A video of the event is available here

He said that the World Bank has also supported several Caribbean countries in their efforts to determine the feasibility of offshore wind—Barbados, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, and the Dominican Republic—and that the Caribbean Development Bank has also worked on this issue.

The Latin American and Caribbean region as a whole has “thousands of gigawatts of potential” in offshore wind, Leybourne said. “Some of the wind conditions are the best in the world. The resource is there, it’s clear.”

At the Hywind Tampen floating wind farm in the North Sea, within sight of the Mongstad refinery on the coast of Norway, a tugboat prepares to tow one of the turbines. Credit: Jan Arne Wold / Equinor

That doesn’t mean that offshore wind is an appropriate solution for every country. As the experts on the panel explained, many factors come into play. In some cases, the best wind resources are too far away from the major load centers where the electricity is needed and the cost of building new transmission lines would make a project prohibitive. Some places, meanwhile, may have plenty of land available for onshore wind projects, which are less costly to develop. Other places may not have enough domestic demand for electricity to justify an investment in offshore wind.

For some countries, offshore wind may be viable not for local or regional electricity consumption but for the production of green hydrogen to help meet the expected global demand. “I believe that’s going to be the main driver,” said Leila Garcia da Fonseca, who is responsible for wind and solar market research for the American region at Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables.

Even when circumstances are conducive to offshore wind development, turbines will not spring up overnight. “Offshore wind power is not something you can develop from one year to another. It takes time,” said Ramón Fiestas, who chairs the Latin America Committee for the Global Wind Energy Council, a trade association for the wind power industry.

How much time depends in part on each country’s experience in such areas as environmental licensing, onshore wind projects, and even offshore oil and gas development, Fiestas said.

In fact, because of the large scale and complexity of offshore wind projects, several of the experts said, the process required for getting a project up and running more closely parallels what happens with the offshore petroleum industry than with onshore wind.

The Hywind Tampen floating wind farm is assembled in the municipality of Gulen, Norway. The wind farm, which began producing power last November, has a capacity of 60 MW. Credit: Ole Jørgen Bratland / Equinor

“Offshore wind really is not onshore wind in the sea,” Leybourne said. “It’s very, very different from a solar project, it’s very different from these small-scale projects that we’ve got that governments are used to dealing with.”

Governments interested in pursuing offshore wind need to become actively involved in long-term planning, Leybourne said, and should appoint a focal agency to coordinate all the different institutions and stakeholders that have a role. They need to establish clear requirements and procedures for permitting, he added, and must also do environmental and social impact assessments that meet international standards, since this will be a requirement for obtaining international financing.

Having a regulatory framework in place for offshore wind is “a no-brainer,” said Brazilian energy expert Thiago Barral.

“It’s just a matter of putting the rules for investment to be done in a technology that is clean and proven to be valuable for the energy transition and [for] increasing energy security,” he said. (At the time of the Inter-American Dialogue event, Barral headed Brazil’s Energy Research Office, a government institution responsible for energy planning studies; now, he serves as Secretary for Energy Transition and Planning at the Ministry of Mines and Energy.)

A blade is installed on one of the turbines for the Hywind Tampen floating wind farm. Credit: Jan Arne Wold / Equinor

One obstacle to offshore wind is that it’s still expensive, though costs fell by half between 2015 and 2020, according to Wood Mackenzie research. Several panelists discussed how or whether governments should help get the market off the ground through subsidies or other incentives.

The costs of a country’s first projects are always higher than subsequent ones, Leybourne pointed out. As the industry matures, acquires experience, develops local content, and reduces risks, the cost of capital comes down and projects become more affordable.

“I think there does need to be some level of support for these first projects to kick-start a market and start that cost-reduction journey,” he said.

When considering costs, Barral said, it’s important not to simply compare one energy technology with another but to look at the big picture. This is something that was driven home in Brazil in 2021, he said, when drought put pressure on the country’s hydroelectric sources.

“We must have a holistic approach towards cost, and that means that we must understand how offshore wind will help us with the flexibility issues raised with massive integration of renewables,” he said, adding that it “can help us with firm capacity need requirements to be more climate-resilient.”

“There are many issues that must be addressed when we discuss about cost and cost comparison,” Barral said. “We have to have a system perspective not to be unfair to these new technologies.”

For Ramón Fiestas, the driving factor should not be cost but the urgency of having a decarbonized energy sector, accelerating the energy transition, and meeting the climate commitments that countries have made through the Paris Agreement. Making that happen will require political will, he stressed.

It’s also important to consider the cost of not having offshore wind, he said, adding that the Russian invasion of Ukraine served as a reminder of the need to secure a reliable energy supply.

“This is about energy security. This is about decarbonizing economies,” he said. “This is not about costs anymore.”

View Map

View Map