No doubt about it, July 2022 was hot in the world’s northern latitudes—the third-hottest July on record for the United States and the sixth-hottest on record for the planet, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Globally, the agency said, this was the 46th consecutive July and the 451st consecutive month in which temperatures exceeded the 20th century average.

“The five warmest Julys on record have all occurred since 2016,” NOAA reported.

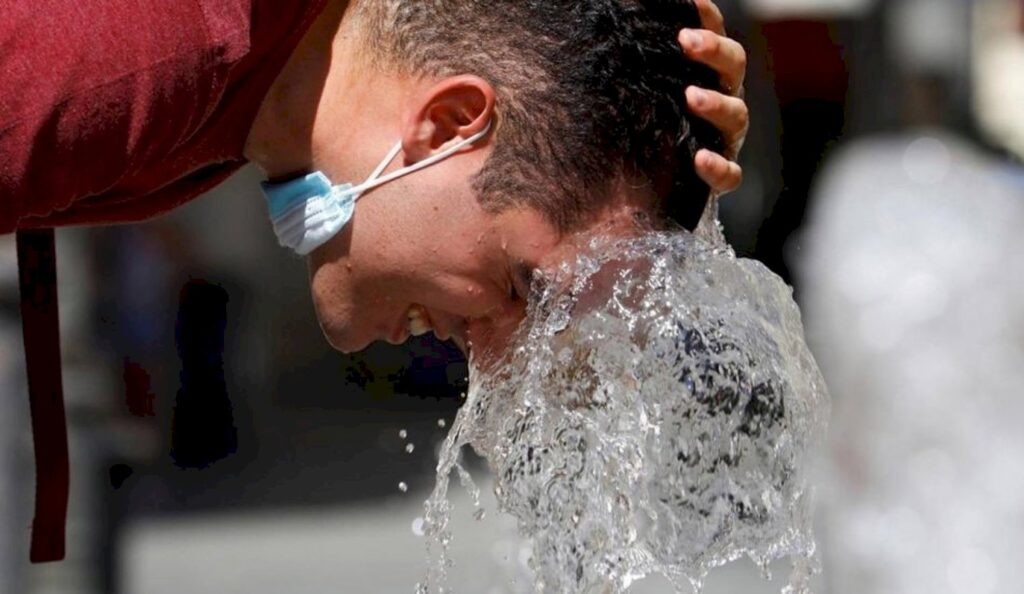

Higher temperatures can worsen drought conditions, fuel wildfires, strengthen storms, alter weather patterns, ruin crops, and produce all sorts of other large-scale environmental impacts. They can also wreak havoc on the human body.

“Heat kills,” said the Regional Director for Europe of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr. Hans Henri P. Kluge. In a statement on July 22, he said the protracted heat wave that was engulfing much of Europe at the time was to blame for more than 1,700 deaths in Spain and Portugal alone.

Extreme heat, Kluge said, can exacerbate pre-existing health conditions and cause heatstroke and other forms of hyperthermia (an abnormally high body temperature), leading to suffering and premature death. “Individuals at either end of life’s spectrum—infants and children, and older people—are at particular risk,” he noted.

Excessive heat can intensify wildfires, such as this one near Beaumont, California, in 2020.

In the Spanish city of Seville, July’s heat wave was so severe that it was given a name: Zoe. The idea—implemented as part of a pilot project called proMETEO Seville—is to start treating intense heat episodes like hurricanes, naming and ranking them to raise public awareness of the impacts of extreme heat on health and to promote measures to minimize these impacts. Instead of an A-to-Z naming system, the heat alerts will work through the alphabet backwards.

ProMETEO Seville is an initiative of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. Two years ago, the organization launched the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance, bringing together partners from around the globe to tackle the problem, focusing especially on the way extreme heat affects vulnerable people living in cities. Working in collaboration with the UN Environment Programme, among other partners, the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance developed a tool called the Heat Action Platform, which aims to identify solutions to build resilience to extreme heat.

With support from the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance, several cities around the globe have now appointed Chief Heat Officers (CHOs) to focus on this problem. In March, the Metropolitan Regional Government of Santiago de Chile became the first urban area in South America to create such a position, appointing Cristina Huidobro—who heads the regional government’s Resilient Urban Projects Unit—as its first CHO.

In a report this year, the organization Sustainable Energy for All said that worldwide, “1.2 billion rural and urban poor are at high risk because they lack access to cooling.” One study published last year in the medical journal The Lancet estimated that 356,000 deaths in 2019 were linked to extreme heat.

“What the health consequences of a hotter climate are and how extreme heat is managed will be two of the defining questions of this decade,” the publication’s editors wrote.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 3,066 heat-related deaths between 2018 and 2020, with the highest percentage (19%) occurring among people between the ages of 55 and 64.

Heat was a contributing factor in 1,577 deaths in the United States in 2021, according to an analysis of the CDC’s provisional mortality statistics by the company ValuePenguin. The study found that two Western states had by far the highest overall death rates from heat between 2018 and 2021: Nevada, with an annualized rate of 4.54 deaths per 100,000 residents, and Arizona, with a rate of 4.46.

But people can die from the heat nearly anywhere. In 2021, a heat wave in the Canadian province of British Columbia caused 569 deaths from June 20 to July 29, according to the BC Coroners Service. This summer has again brought periods of soaring temperatures to British Columbia and other areas normally associated with much cooler summer weather, such as the Pacific Northwest of the United States.

During a heat wave in São Paulo, Brazil, a street thermometer on Paulista Avenue registered a temperature of 41 degrees Celsius (105.8 Fahrenheit).

The risks of heat-related illness and death tend to be higher in cities, where buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and retain heat, creating what is known as the “urban heat island effect.”

That makes Latin America especially vulnerable, as it is one of the most urbanized regions in the world, said Dr. Josiah Kephart, the lead author of a recent study done as part of a project called Salud Urbana en América Latina (SALURBAL), “Urban Health in Latin America.”

Another factor, Kephart said, has to do with demographics. The percentage of older people in the population of Latin America is increasing faster than the global average, he said, and people tend to be more susceptible to heat as they get older. Those two factors combined with climate change add up to “three intertwined challenges,” he said in an interview.

“We would expect that they would really feed into each other to make extreme heat in particular be a really serious health problem within the region,” he added. Kephart has been a post-doctoral fellow with the SALURBAL project and on September 1 becomes an Assistant Professor at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health.

The recent SALURBAL study, titled “City-level impact of extreme temperatures and mortality in Latin America,” estimated excess deaths from “nonoptimal temperatures” in 326 cities across nine countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, and Peru. The temperature considered “optimal” varies from place to place, Kephart said, but it is generally what people think of as room temperature—usually between 20 and 25 degrees Celsius (68 and 77 Fahrenheit), averaged over a 24-hour period. It is the point where the risk to the human body is the least, he said.

The study looked at daily death records for the hottest and coldest 18 days in each city every year from 2002 through 2015. It found that more deaths are attributable to extreme cold than to extreme heat over the course of a year—a finding consistent with global studies—but sharp increases in heat can have devastating health effects, especially in places that are not used to such high temperatures.

“For extremely hot days, the risk of mortality rises very steeply,” Kephart said. “We found that a single 1-degree Celsius higher temperature within those 18 hottest days was associated with almost a 6% higher risk of death.”

And the percentage increases proportionately with larger increases in temperatures. “That’s a lot of death,” Kephart said. “It’s a big number for this kind of commonplace environmental factor”—especially, he added, considering that hot days are projected to become not only hotter but more frequent as climate change continues to intensify.

The study was based on official government death records in each country. Due to data limitations, it could not cover every potential heat-related cause of death, Kephart said, noting that some studies have linked heat to increases in homicides, traffic fatalities, and deaths by drowning.

The SALURBAL study focused primarily on cardiovascular and respiratory deaths. It found, for example, that people suffering from respiratory conditions—whether chronic diseases like asthma or acute respiratory infections—had a harder time dealing with the extra physiological stress on the body when temperatures were hot.

Temperatures soared in Argentina during a heat wave in January 2022.

“If you’re exposed to extreme heat, your body has to put out a lot of effort trying to cool you down,” Kephart said.

Launched in 2017, SALURBAL is an international project that involves academic institutions from 11 Latin American countries. It is coordinated by the Urban Health Collaborative at Drexel University, based in Philadelphia, and funded by a global charitable foundation called the Wellcome Trust.

Health professionals have long held that the health effects of climate change merit more study and attention, but only recently has the health dimension begun to emerge as a more important issue on the global climate agenda, according to Dr. Ana Diez Roux, Dean of Drexel’s Dornsife School of Public Health and the principal investigator for SALURBAL.

“I think there’s a shift to really taking seriously the health implications,” she said. It’s a complicated topic with many different aspects, she said. Of course, climate change can increase and exacerbate natural disasters that injure and kill people, but it can also have less obvious health effects.

She cited another recent SALURBAL study that examined the relationship between ambient temperature and birthweight in Latin American cities, given that pregnant women have a reduced ability to regulate their body temperature because of the increased metabolic demands of pregnancy. “Higher temperatures during the entire gestation are associated with lower birthweight, particularly in Mexico and Brazil,” the study found.

Diez Roux said there is a growing discussion in public health about whether, and how, people and cities can adapt to rising temperatures. “Most of the adaptation is not biological, it’s actually social processes,” she said in an interview. This might involve changing practices so that people are not outdoors at certain times of day—which in turn could lead to adjustments in work and recreation habits.

Communities can help to reduce the amount of urban heat by expanding green spaces.

Another positive sign, she said, is the increased recognition of the potential “co-benefits” of measures taken to mitigate climate change. A city that expands its green spaces to promote walking and bicycle transportation will strengthen public health not only by reducing pollution but also by increasing people’s physical activity and helping to reduce the amount of urban heat.

Cities don’t have any time to lose, according to Josiah Kephart. “We need to be planting the trees now for the heat that we’re going to experience 20 years from now, because it’s only going to get worse as far as the current projections go.”

View Map

View Map