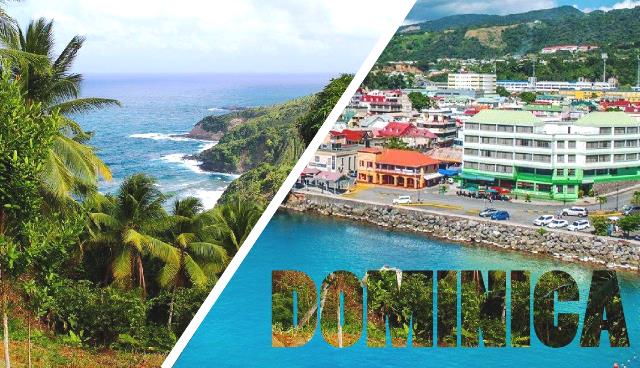

One year after Hurricane Maria stripped Dominica’s trees of their leaves and turned the lush Caribbean island to brown, Ambassador Vince Henderson reports that nature is rebounding. “The island is looking green again, and I think psychologically that makes a big difference,” he said recently, just days after returning from a visit home. In an interview, the diplomat talked about the resilience of his fellow citizens and some of the steps his country is taking to become more resilient to climate change.

One year after Hurricane Maria stripped Dominica’s trees of their leaves and turned the lush Caribbean island to brown, Ambassador Vince Henderson reports that nature is rebounding. “The island is looking green again, and I think psychologically that makes a big difference,” he said recently, just days after returning from a visit home. In an interview, the diplomat talked about the resilience of his fellow citizens and some of the steps his country is taking to become more resilient to climate change.On a day-to-day level, Henderson said, there’s already “a world of difference” between today and last September, when Maria made landfall at Category 5 strength. Not only is vegetation coming back; so are many of the residents who had headed to other islands or to Europe or the United States after the storm.

“There were a lot of people who left, but a lot have returned,” said Ambassador Henderson, who represents his country at the Organization of American States (OAS) and before the U.S. government.

Cable TV and internet services can still be iffy in places, but most basic services are functioning again, and 93% of the population has access to electric power, according to Henderson. However, he added, about a third of the island’s residents are still unable to reconnect to the grid because their homes or businesses are too damaged.

“If your house doesn’t have a roof, then obviously you can’t be certified and can’t be connected,” Henderson explained.

Dominica suffered an estimated $1.3 billion in damage from Maria—226 percent of GDP. The International Monetary Fund expects the country’s economic output to decline by 14 percent this year and take about five years to recover to pre-Maria levels.

In response to the magnitude of the challenge, Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerritt has vowed that Dominica will become the world’s first “climate-resilient nation.” (See related ECPA story, Starting Over: Building Resilience in the Face of Disaster.)

Earlier this year, the government launched the Climate Resilience Execution Agency of Dominica (CREAD) to coordinate and implement its long-term efforts in this area. James Fletcher, a former Minister of Sustainable Development of Saint Lucia, has been appointed to lead the new agency, which is receiving start-up financial backing from the United Kingdom.

International donors are starting to implement a wide range of projects in different sectors in Dominica. Funding from the World Bank will help restore fishing fleets, farms, and housing destroyed by the storm; meanwhile, Canada recently announced an initiative to rebuild several schools.

Understandably, given the urgent message Hurricane Maria delivered about climate change, Dominica’s plans on the energy front are sparking particular interest among donors. France is funding a study on how to make the electricity grid more resilient; the European Union is supporting an effort to bring solar power with battery storage to ports and other key infrastructure; the Clinton Climate Initiative is helping design an Integrated Energy Resource Plan to determine the right mix of renewables.

Dominica is moving forward on its plans to develop its abundant geothermal resources, Ambassador Henderson said. Although last year’s hurricane set back the project by about six months, he said, construction should begin early next year on a 7-megawatt geothermal plant and reinjection well. The project, which could be in operation by late 2020, is expected to supply about one third of the country’s energy needs. The power will be produced by the government-owned Dominica Geothermal Development Company and transmitted and distributed to customers through a power purchase agreement with Dominica Electricity Services, Ltd. (DOMLEC), the mostly privately held utility that serves the island.

The government has already invested $9 million to drill production wells, and the overall project will require about $33 million more, according to Henderson. The project is receiving major concessional financing from the World Bank, with additional funding coming from New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and SIDS DOCK, an energy initiative geared toward small island developing states.

Design modifications have been made since the hurricane to build in more resilience by burying the lines that connect the geothermal plant to the electric distribution system, Henderson said. He added that it’s possible other power lines on the island may be placed underground too, especially in larger population centers.

Dominica—which, like Puerto Rico, has rugged mountainous areas— is also looking at how to harden its aboveground transmission and distribution system against future storms. And solar microgrids with battery storage could provide “planned islanding,” especially in smaller, more remote communities, Henderson said.

“In the event the main transmission lines are down, you could simply just generate power from within that area” he explained.

Although distribution and transmission tend to be the most vulnerable aspects, the power generation infrastructure also needs hardening. Maria damaged a small hydroelectric plant, as well as a diesel generator that was housed in a building destroyed by the storm.

When Ambassador Henderson was in Dominica recently, residents were bracing for a potential hit from Hurricane Isaac. It ended up weakening and changing direction—a headline in one Caribbean newspaper read “Skerritt thanks God as Isaac moves into sea”—but for a while, people went into full “preparation mode,” Henderson said.

“Even if it was just a Category 1 hurricane, people took precautions as if it were a Category 5,” he said. After an experience like Maria, “you always feel that you have to get prepared, because you saw what happened, you know what to expect.”

Henderson himself was home during Maria and lost the roof to his house, so he can understand the lingering effects of such an experience. “I think that people are still traumatized. I was for a while, to be honest.” At the same time, he knew it wouldn’t take long after the threat of Isaac for everyone to be “back building and trying to get things going and trying to put their lives together again.”

“People have more resilience than sometimes we would think,” he said.

View Map

View Map