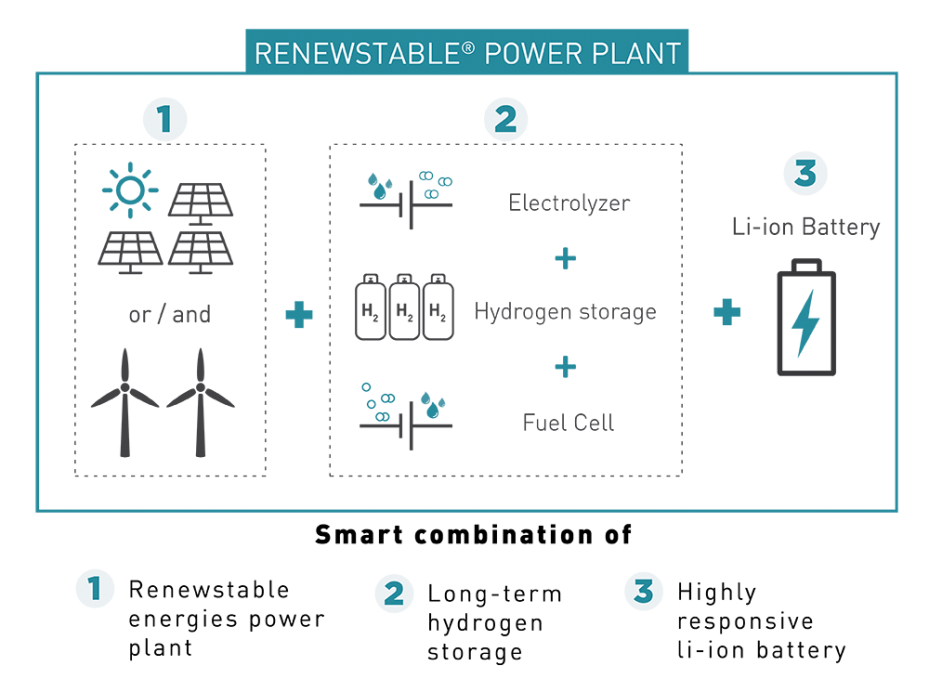

HDF Energy—the acronym stands for Hydrogène de France—is building a solar-hydrogen power plant in French Guiana, with similar projects in the works in Barbados, in the Mexican state of Baja California Sur, and elsewhere in the Americas. The company has trademarked the name Renewstable to describe these hybrid systems.

Each plant is designed to include a large solar farm. Some of the electricity generated by the solar panels will feed directly into the grid; the excess power will run an electrolyzer, a system that splits water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen gas produced through that process will be stored on site and will be available to generate electricity on demand, using fuel cells. The system also includes lithium batteries, which will provide short-term storage and can kick in instantaneously when needed, delivering flexibility and quick response.

The combination of components means that the power plant will be able to deliver clean baseload energy, 24/7, as reliably as a thermal plant that burns fossil fuels, according to Cristina Martín, the company’s Vice President for Latin America, and Thibault Ménage, Vice President for the Caribbean.

This type of hybrid system is intended to help solve the conundrum of how to maximize the use of renewable energy without losing grid stability. This is a particularly thorny problem in small power systems that are not interconnected with other grids, such as in small island countries or “energy islands” within larger territories.

To maintain a stable frequency, an electric power grid must keep supply and demand in balance at all times. A large power system with plenty of generation assets and interconnections to neighboring grids has different options on hand to maintain that balance to the millisecond, but that is not necessarily the case in a small, isolated system. Too much intermittent power in a small system—too many “electrons that you don’t control,” as Ménage put it—can lead to blackouts.

“What we market with our project is locally produced, constant power which is stable,” he said in an interview.

A solar-hydrogen or wind-hydrogen plant can help small countries meet their goals for decarbonizing the electricity sector, Ménage said. And, he said, the fact that these hybrid plants will not rely on imported fossil fuels is a critical consideration—especially at a time like the present, when the Russian invasion of Ukraine has driven up fuel prices and disrupted global supplies.

“Energy security right now is key,” Ménage said. In addition to the Barbados project, he said, HDF Energy is exploring the possibility for similar projects in other island states in the English-speaking Caribbean, specifically those that lack geothermal potential.

Although these types of projects would not yet be cost-competitive everywhere, they do make economic sense in certain places, Cristina Martín said in a separate interview. The capital expenditure is enormous, she explained, but the operating expenditure is low. Traditional thermal plants require much less upfront investment but cost far more to run, because they require a constant supply of fuel, often expensive diesel or heavy fuel oil.

Martín said she is looking at the potential for projects in four other countries in Latin America in addition to Mexico: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador. One possibility under discussion is a small power plant on San Cristóbal Island in the Galápagos archipelago.

Discussions are underway for a small power plant on San Cristóbal Island, in the Galápagos.

Construction is already underway on the first of HDF Energy’s Renewstable projects, a $200 million plant in French Guiana, an overseas region of France located on the northeastern coast of South America. The plant, called CEOG (Centrale Electrique de l’Ouest Guyanais), will provide 10 megawatts (MW) of firm power by day and evening and 3 MW at night.

A company news release in September 2021 announced the financial close and groundbreaking for the project, which it called “the world’s first baseload renewable energy power plant using hydrogen technology.” The announcement said that the plant will operate under a 25-year power purchase agreement signed with the French utility EDF.

HDF Energy’s equity partners in that project are the infrastructure fund Meridiam and the petroleum operator SARA (Rubis Group), and CEOG has received non-recourse project financing from commercial and development banks, according to the announcement. (Non-recourse loans are typically secured only by the assets being financed.)

Meanwhile, construction could begin as early as next year on the projects under development in Barbados and Mexico, although neither is yet a done deal, Ménage and Martín stressed.

The Barbados project is designed to serve about 16,000 customers. Rendering courtesy of HDF Energy.

The Barbados project is designed to supply 13 MW of firm power in the daytime and evening and 3 MW at night, serving about 16,000 customers. The site selected is in the parish of Saint Philip, on the southeastern part of the island, on what was once a sugar cane plantation.

In this case, the solar panels will have some company: more than 1,800 Blackbelly sheep. That component, which grew out of the government’s desire to keep the land in the agricultural sector, will maximize the land’s productivity, provide an additional revenue stream for the country, and contribute to food security, according to Ménage. HDF will not run the sheep farm; that task will be handled by a farming operation that is already grazing sheep on another solar farm on the island.

Although incorporating a sheep farm into the power plant project has required some additional work, Ménage said, the grazing sheep will provide some benefit to the plant too, by keeping the grass from growing too high around the panels, thus reducing the fire hazard.

Ménage said that the project is going through the permitting process, and negotiations are about to begin on a long-term power purchase agreement with Barbados Light and Power Company. The utility, which is owned by the Canadian company Emera, generates, transmits, and distributes electricity to some 131,000 customers on the island.

Rubis, an independent French operator in the energy sector, is an equity partner not only in the CEOG project but in Renewstable Barbados too; in February, HDF Energy announced that Rubis had acquired a 51% stake. HDF Energy plans to sell 30% of the project to local shareholders and has been in discussions with the Barbados Sustainable Energy Co-operative Society about this potential investment, according to the company.

Energía Los Cabos would supply 40 MW of firm power in the daytime and evening and 9 MW at night to tourist destinations on the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula. Rendering courtesy of HDF Energy.

The project in development in Mexico is considerably larger than the one in Barbados; it would supply 40 MW of firm power in the daytime and evening and 9 MW at night. The electricity produced would serve customers in tourist destinations in the southernmost part of the Baja California Peninsula.

The two states that make up the peninsula do not have interconnected grids, largely because that would require building major transmission lines across vast stretches of desert, according to Cristina Martín. The grid in Baja California Norte is interconnected with the power system in the U.S. state of California, she said, but the grid in Baja California Sur “functions like an energy island.”

Over the years, various options have been discussed to lay an underwater cable to connect the southern part of the peninsula with the mainland, but these proposals have not come to fruition.

Today, most of Baja California Sur’s electricity is generated by thermal power plants that burn heavy fuel oil in the port city of La Paz. The electricity then travels south via medium-tension transmission lines to the booming resort cities of San José del Cabo and Cabo San Lucas. “The losses are enormous,” Martín said.

HDF Energy has secured a long-term lease on communally owned land (ejido) near San José del Cabo. The size of the proposed plant is equivalent to one of four units at the power plant in La Paz, as a way to demonstrate that one of these units can be taken out of operation without compromising the performance of the grid, according to Martín.

The idea with this project, she said, is that Mexico’s publicly owned utility, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), would not only be the energy offtaker—in other words, the purchaser of the power—but the plant’s majority shareholder. HDF Energy and the CFE have a memorandum of understanding in place, but no commitment has yet been reached and negotiations are still underway, Martín said.

View Map

View Map