First, a bit of context. Valdivia sees more than its share of gray skies and chilly days. Snow is rare, but rain is anything but; the city’s annual rainfall is more than 2,400 millimeters (about 95 inches). Most homes burn firewood for heat, and even many public buildings have wood-fired boilers, which often operate eight or nine months out of the year.

Valdivia was one of three sites chosen for an energy efficiency project carried out by Florida International University (FIU), in partnership with the Universidad Austral de Chile, through the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA). Similar efforts were also implemented with local partners in Goiás, Brazil, and Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. The goal was to assess energy use in selected municipal buildings and develop cost-effective recommendations that could be applied more broadly.

The project team in Valdivia picked three different schools to study, each made of different materials and built in different eras. It also decided to evaluate the building that houses City Hall.

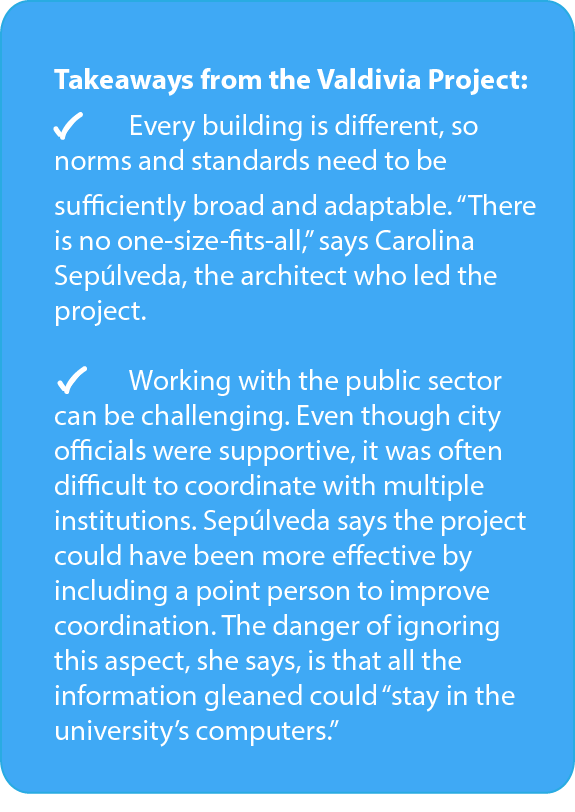

The biggest challenge was to determine just how much energy the buildings were already using and how effectively—not as simple a task as it sounds, according to Carolina Sepúlveda, an architect at the Universidad Austral de Chile who directed the three-year project.

Her team did a top-to-bottom assessment of each building that included onsite observations and interviews with regular users: How comfortable did the room feel? Did the temperature vary from morning to afternoon? Was the lighting adequate on cloudy days?

Answers often varied widely, depending on the person and the building. At City Hall, employees in one area were always too cold, while those on another floor might be sweating. At the schools, the teachers tended to complain more about the temperature than the students—but then again, they were the ones who had to deal with fidgety pupils when the classroom was too hot or cold.

The team took all the qualitative information and cross-checked it against quantitative data. It used computer simulations to create a 3-D analysis of each building, and installed interior and exterior sensors to scientifically track energy performance over time. After all, without a clear starting point it would be impossible to accurately measure progress.

“The main work of this project was to establish that baseline,” Sepúlveda explained. Using that information, the project team is developing a range of materials, including a complete report with guidelines and recommendations, an educational book for children on saving energy, and detailed architectural specifications based on the results of the study.

Given funding limitations, the project was unable to implement the whole range of recommendations—insulating the classrooms, for example, is something that would require significant public funding—but it could at least start with better lighting. The Escuela Rural Misión de Arique, a small rural school built out of wood in the 1960s, became the first in the Valdivia school district to have 100 percent LED lighting—a step that cut its electricity consumption by more than 15 percent. The Chilean Energy Ministry’s Regional Secretariat has made a commitment to continue to implement improvements across the city’s schools as funding from the federal government becomes available, Sepúlveda said.

Given funding limitations, the project was unable to implement the whole range of recommendations—insulating the classrooms, for example, is something that would require significant public funding—but it could at least start with better lighting. The Escuela Rural Misión de Arique, a small rural school built out of wood in the 1960s, became the first in the Valdivia school district to have 100 percent LED lighting—a step that cut its electricity consumption by more than 15 percent. The Chilean Energy Ministry’s Regional Secretariat has made a commitment to continue to implement improvements across the city’s schools as funding from the federal government becomes available, Sepúlveda said.

Lighting improvements were also made in the windowless basement of City Hall, a high-traffic area where members of the public go to get their driver’s licenses renewed. “I myself have been there for two hours,” said Sepúlveda, who is glad the city’s drivers no longer have to wait under flickering fluorescent lights.

View Map

View Map