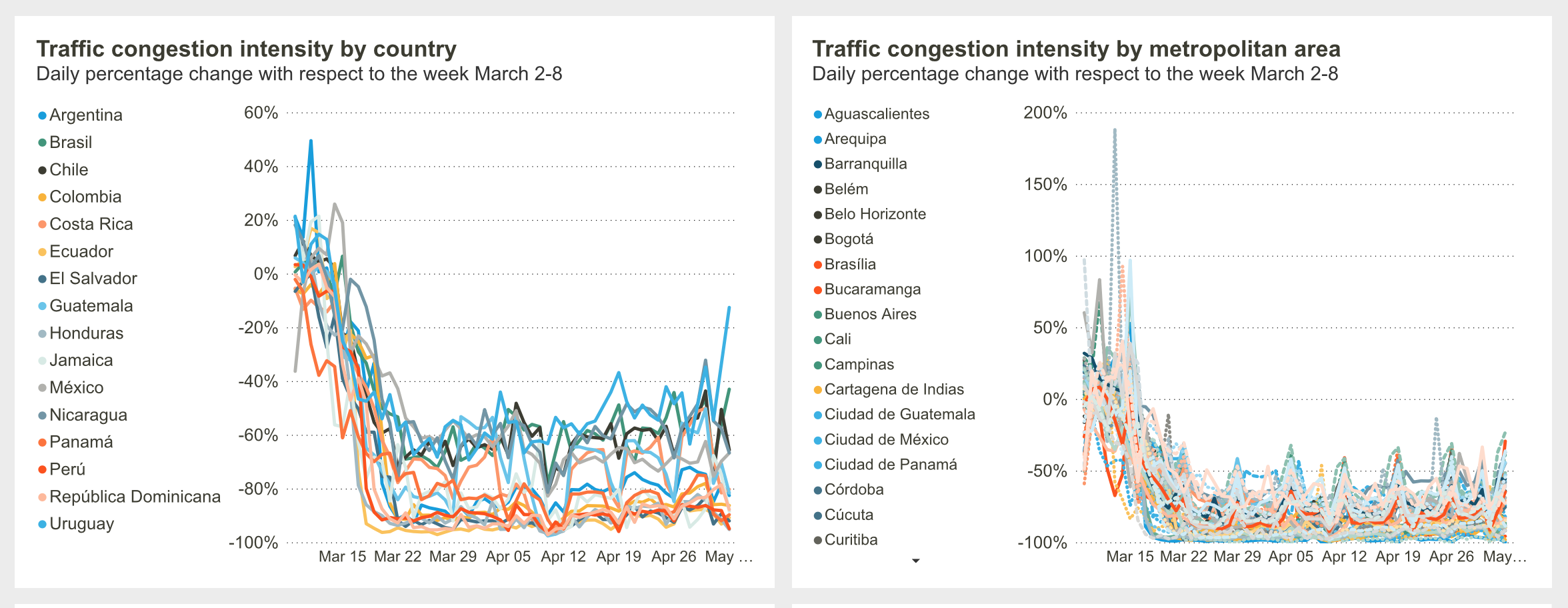

The lockdowns implemented to slow down the spread of Covid-19 have varied considerably from country to country and city to city, in scope, intensity, enforcement, and timing. In general, though, a large percentage of the traffic normally encountered throughout the region came to a standstill for several weeks.

A Coronavirus Impact Dashboard created by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) shows steep declines in traffic congestion throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, beginning the week of March 15. By late April, congestion in some cities was down by more than 90% when compared with the first week in March, based on data from the Google navigation software Waze.

Preliminary studies are starting to document some of the changes in air quality as a result of Covid-19. One report issued by the Swiss company IQAir looked at the results of three-week lockdowns in 10 cities around the world. It found that levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) declined by almost a third in São Paulo and 25% in New York City. Los Angeles had its longest stretch on record of meeting the air quality guidelines established by the World Health Organization, the report said.

Air quality has an enormous impact on public health. In fact, researchers at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health recently found that higher levels of fine particulate matter were associated with higher death rates from Covid-19. Their analysis, which has been submitted for peer review, looks at data from more than 3,000 counties in the United States.

During a webinar held on April 16 by the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA), several experts who monitor air quality in Latin American cities dug into some of the data they had been seeing since the shutdowns began.

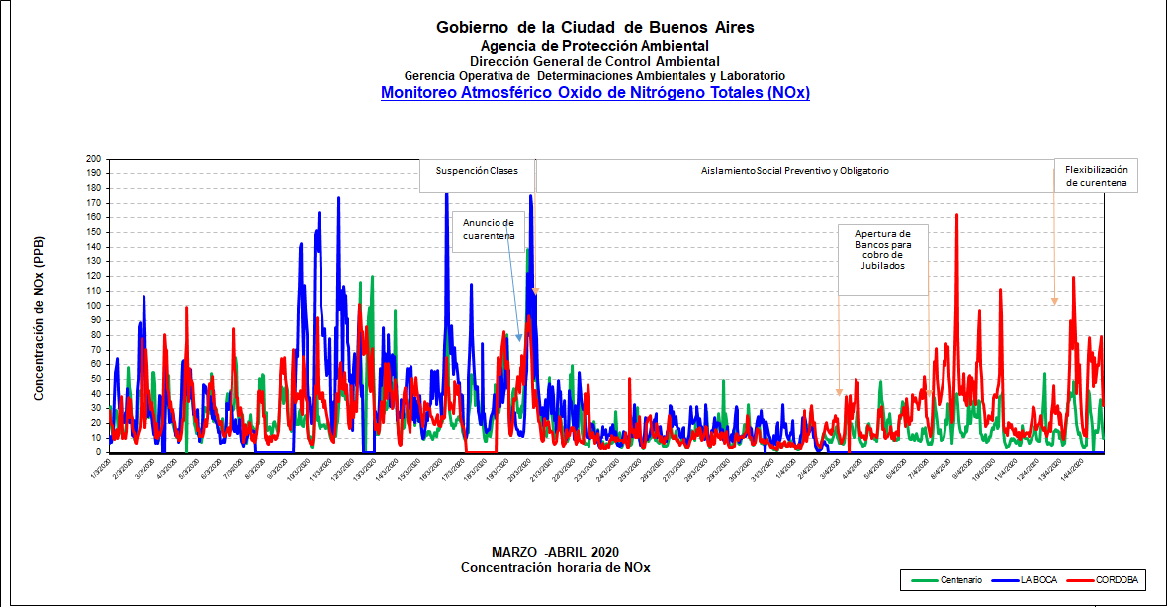

María Inés de Casas, who runs the City of Buenos Aires Air Monitoring Network, showed a photo of the iconic obelisk that stands in the middle of the city’s broad Avenida 9 de Julio. In the photo—taken at the height of the mandatory quarantine—the multiple lanes are almost completely devoid of vehicles, and the sky is bright blue.

Like several other presenters, de Casas shared detailed charts and graphs depicting the concentration of some of the main air pollutants from day to day, as measured at different monitoring stations throughout the city. In the case of Buenos Aires, the level of air pollution spiked when it was announced that a mandatory quarantine was about to go into effect, and everyone rushed out to get provisions; this was followed by a steep, sustained drop in pollution for two weeks, during the total lockdown, then gradual increases as some restrictions on economic activity started to ease.

The decreases, which were noticeable throughout the period of quarantine, confirmed the city’s primary source of air pollution, de Casas said. “While we always expected that vehicles were mainly responsible, with all these measurements we are seeing that in fact that hypothesis is correct,” she said.

Measurements of air quality typically look at six “criteria air pollutants” known to harm human health: carbon monoxide, lead, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ground-level ozone, and particulate matter. (See previous stories, Developing Credible Data on Air Quality and Putting Air Quality to the Test.)

All sorts of factors can affect pollution levels, including elevation, climate, and geography. A city surrounded by mountains will likely have a harder time dispersing pollution than one located on a windy plain. The sources of pollution can also vary, as has been evident in some cities during the quarantines of the past two months.

In Colombia, wildfires burning across large parts of the country produced particulate matter that kept pollution levels high for more than a week after the quarantine began, according to Tiberio Benavides of the Air Quality Laboratory on the Medellín campus of the National University of Colombia. It wasn’t until the fires began to die out and seasonal rains began to fall that the effects of lower pollution from vehicles became visible in cities such as Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali, he explained.

Once the drop in pollution arrived, it was dramatic; a graph shows that in the first week of April, average PM2.5 concentrations plunged to the lowest point seen in Medellín in the last five years.

In Santiago, Chile, the differences in levels of air pollution were measurable but less pronounced—in part because the lockdown applied to only 7 of the 32 municipal subdivisions that make up the province of Santiago. Together, these represent 26% of the province’s population and about 36% of its vehicles, according to Isabel Leiva of the national Superintendency of the Environment.

She looked at the period between March 26 and April 6, taking data from three monitoring stations in the quarantined area and one outside to serve as a control. Cautioning that not too much should be read into data for such a short period, Leiva noted that the biggest declines in most air pollutants were seen in the eastern part of the city, in a largely residential area known as Las Condes.

All the monitoring stations registered ozone levels that were slightly higher than in recent years, which Leiva attributed to relatively high temperatures at the end of the summer in Chile.

Ozone concentrations have also been high in Mexico City, which is typical for this time of year but in this case has been exacerbated by two factors, according to Olivia Rivera Hernández, Air Quality Director for the city’s Secretariat of the Environment. The first is unusually high temperatures, she said, noting that for the first time in 30 years, the city hit a high of 31.9 degrees Celsius (89.4 Fahrenheit) during the month of March.

Another factor is a well-documented, if perverse, phenomenon known as the “ozone weekend effect,” in which chemical changes in the air produced by declines in nitrogen oxides can actually lead to increases in ozone. While Mexico City saw “drastic” reductions in some pollutants beginning the week of March 23, ozone went up, Rivera said. She said that the current government is making a concerted effort to tackle high ozone levels by reducing another contributor to the problem, volatile organic compounds emitted by evaporated gas, cleaning products, and other sources.

In cities that have observed major improvements to their air quality in recent weeks, the question is whether these visible changes will spur long-lasting changes in behavior. In a video released on Earth Day, Peru’s Ministry of the Environment noted that the country was seeing skies as clear as 50 years ago, more birds and wildlife, and cleaner waters.

“This emergency that we are experiencing is a wake-up call from our Mother Earth, who warns us that if we want to stay healthy, we must also keep her healthy,” José Álvarez, Director General of Biological Diversity, said in the video. He ended with a pointed question: “As for you, what will you do when all this is over?”

View Map

View Map