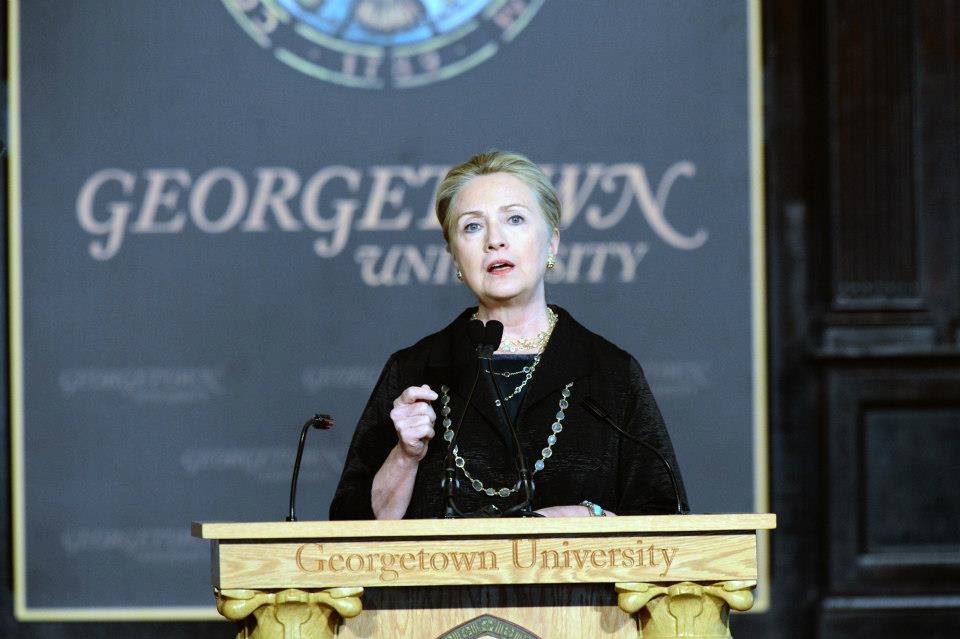

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton

On Energy Diplomacy in the 21st Century

October 18, 2012

Georgetown University

Washington, D.C.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Thank you. Well, it is wonderful to be back here at Georgetown

and in one of the most beautiful venues not only in Washington but anywhere, to have this

chance to talk with you about an issue that will definitely shape your futures, and to share with

you some thoughts about what that actually means.

As Dean Lancaster said, I am a Hoya by marriage. (Laughter.) I am so proud to be that, and so

grateful for the extraordinary contribution that the School of Foreign Service makes to the State

Department. We are enriched every single day, Dean Lancaster, by the work and scholarship

that goes on here at this great university.

So I came here because it’s not only that young people have a great stake in our policies at

home and abroad about energy, but because we all have to work together to find answers to

some of the challenges that it poses. Energy cuts across the entirety of U.S. foreign policy. It’s

a matter of national security and global stability. It’s at the heart of the global economy. It’s

also an issue of democracy and human rights. And it’s been a top concern of mine for years,

but certainly these last four years as Secretary of State, and it is sure to be the same for the next

Secretary.

So here today, I want to talk about the vast changes taking place regarding energy worldwide

and what they will mean for us. America’s objectives for our energy security and our progress in

other places is critical, and the steps that we are taking to try to achieve those objectives are ones

that I want briefly to outline to you.

But let me start with the basics. Energy matters to America’s foreign policy for three

fundamental reasons. First, it rests at the core of geopolitics, because fundamentally, energy is

an issue of wealth and power, which means it can be both a source of conflict and cooperation.

The United States has an interest in resolving disputes over energy, keeping energy supplies and

markets stable through all manner of global crises, ensuring that countries don’t use their energy

resources or proximity to shipping routes to force others to bend to their will or forgive their

bad behavior, and above all, making sure that the American people’s access to energy is secure,

reliable, affordable, and sustainable.

Second, energy is essential to how we will power our economy and manage our environment in

the 21st century. We therefore have an interest in promoting new technologies and sources of

energy – especially including renewables – to reduce pollution, to diversify the global energy

supply, to create jobs, and to address the very real threat of climate change.

And third, energy is key to economic development and political stability. And we have an

interest in helping the 1.3 billion people worldwide who don’t have access to energy. We

believe the more they can access power, the better their chances of starting businesses, educating

their children, increasing their incomes, joining the global economy – all of which is good for

them and for us. And because corruption is often a factor in energy poverty as well as political

instability, we have an interest in supporting leaders who invest their nations’ energy wealth

back into their economies instead of hoarding it for themselves.

So these are the issues that I want to talk with you about today. But before I do, I will

quickly add that many of you, especially students of history, note that these challenges are not

new. Countries have been fighting over resources for centuries. Humankind has always been on

the hunt for new and better sources of energy. And yet this is a moment of profound change and

one that raises complex questions about the direction we are heading.

Right now, for example, in a dramatic reversal, developing countries are consuming more of the

world’s energy than developed countries. China and India’s energy needs are growing rapidly

along with their economies. Demand is also rising across Central Asia and South America

too. There’s been a surge in the global supply of natural gas, creating new opportunities for

gas producers and lessening the world’s dependence on oil. And technology has developed to

the point where we can drill for oil and gas in places like the Arctic and the South China Sea,

opening up new opportunities but also raising questions about our environment and catalyzing

sources of tension.

Now, who will benefit from these changes? Where will we get the energy to meet the world’s

growing needs? How can we make sure that the institutions that kept global energy markets

well supplied in the 20th century, like the International Energy Agency, which the United States

helped to create after the oil crisis in the 1970s, continue to be relevant and effective in the 21 st

century?

And then of course, there are changes here at home that affect the international energy outlook.

Many Americans don’t yet realize the gains that the United States has made. Our use of

renewable wind and solar power has doubled in the past four years. Our oil and natural gas

production is surging. New auto standards will double how far we drive on a gallon of gas. And

for the first time, we’ve introduced fuel efficiency standards for heavy trucks, vans, and buses,

all of which will cut costs. That means we are less reliant on imported energy, which strengthens

our global political and economic standing and the world’s energy marketplace.

Now we all know that energy sparks a great deal of debate in our country, but from my vantage

point as the Secretary of State, outside of the domestic debate, the important thing to keep in

mind is our country is not and cannot be an island when it comes to energy markets. Oil markets

are global and natural gas markets are moving in that direction, many power grids span national

boundaries. Even when Americans are using oil produced entirely within the United States,

the price of that oil is largely determined by the global marketplace. So protecting our own

energy security calls for us to make progress at home and abroad. And that requires American

One year ago this week, after a major strategic review of our nation’s diplomacy and

development efforts, the State Department opened a new bureau. It’s called the Bureau of

Energy Resources, and it’s led, as Dean Lancaster said, by my Special Envoy and Coordinator

for International Energy Affairs, Ambassador Carlos Pascual, who is here today. The bureau is

charged with leading the State Department’s diplomatic efforts on energy. And in the coming

weeks, I will be sending policy guidance to every U.S. embassy worldwide, instructing them

to elevate their reporting on energy issues and pursue more outreach to private sector energy

partners.

Now, make no mistake: In the past, the State Department obviously conducted energy-related

diplomacy – sometimes a great deal of it when specific crises arose. But we did not have a team

of experts dedicated full-time to thinking creatively about how we can solve challenges and seize

opportunities. And now we do. That, in and of itself, is a signal of a broader commitment by the

United States to lead in shaping the global energy future.

And by the way, Dean Lancaster, six members of the State Department’s energy team are

graduates of Georgetown University and they’re here with me today as well. So thank you,

Georgetown. (Applause.) That’s a shameless pitch for the Foreign Service and the State

Department. (Laughter.)

Now we are working in partnership with the Department of Energy, which helps to shape

domestic energy policies and works closely with energy ministries around the world. The

Energy Department’s National Labs are at the cutting edge of innovation, and it has a great deal

of technical expertise, which it brings to bear globally. Its work at home and abroad is critical

because the stronger our domestic energy policies, and the more we advance science and deliver

technical help to our partners, the better positioned we are as a government, and certainly, the

role that the State Department plays to help chart a long-term path to stability, prosperity, and

peace.

Let me speak just briefly about the three pillars of our global energy strategy. First, regarding

the geopolitics of energy, we’re focused on energy diplomacy. Now some of our energy

diplomacy is related to issues in the headlines. You may have read about heated disputes over

territorial claims in the South China Sea. Well, why do you think that’s happening? There are

potentially significant quantities of oil and gas resources right next door to countries with fast-

growing energy needs. And you can see why at times the situation is becoming quite tense. We

are supporting efforts by the parties themselves to adopt a clear code of conduct to manage those

potential resources without conflict.

Now some of our energy diplomacy is focused on remote areas like the Arctic, a frontier of

unexplored oil and gas deposits, and a potential environmental catastrophe. The melting icecaps

are opening new drilling opportunities as well as new maritime routes, so it’s critical that we

now act to set rules of the road to avoid conflict over those resources, and protect the Arctic’s

fragile ecosystem. We’re working to strengthen the Arctic Council, which includes all eight

Arctic nations, including the United States, so it can promote effective cooperation. Last

summer I went up to Tromso, above the Arctic Circle, in Norway, to where the new Secretariat

of the Arctic Council will be based, in order to discuss these issues, which four years ago didn’t

have much currency, but today are being seen as increasingly important.

Another focus of our energy diplomacy is helping to promote competition and prevent

monopolies. Consider what’s been happening in Europe. For decades, many European nations

received much of their natural gas via pipeline from one country: Russia. Few other sources

were available. But that has now changed in part because of the increased production here in

the United States, there’s a lot more natural gas in the global market looking for a home. Plus,

there’s natural gas in the Caspian and in Central Asia. They’d like to sell it, and Europe would

like to buy it. But first, they need to build pipelines. And that’s the goal of a project called the

Southern Corridor, which would stretch across the European continent. The United States has

been an active partner to all those participants to help move this project to fruition.

Now why have we done this? Well, we want to see countries grow and have stronger

economies, but also because energy monopolies create risks. Anywhere in the world, when

one nation is overly dependent on another for its energy, that can jeopardize its political and

economic independence. It can make a country vulnerable to threats and coercion. And that’s

why NATO has identified energy security as a key security issue of our time. It’s also why we

created the U.S.-European Union Energy Council to deepen our cooperation on strategic energy

issues. It’s not just a matter of economic competition, as important as that is. It’s also a matter

of national and international security.

Security is also at the heart of perhaps the most important energy diplomacy we have conducted

in the Obama Administration. I’m sure you know that the United States and the European Union

and other likeminded countries, as well as the United Nations, have imposed sanctions on Iran as

part of our dual-track diplomatic effort to persuade or compel Iran to stop its pursuit of a nuclear

weapon. You may also know that a major target of these sanctions is Iran’s oil industry. What

you may not know, because it doesn’t make headlines, is how much painstaking diplomacy went

into making these sanctions first, adopted, and then, effective.

First, we needed to convince consumers of Iranian oil to stop or significantly reduce their

purchases. At a time when demand for energy is high, many countries understandably were

worried that reducing their purchases would put them in a very difficult position.

So at the same time, we reached out to other major oil producers to encourage them to increase

production so countries would be able to find alternative sources of oil. That was further helped

by the fact that here in the United States we increased oil production by nearly 700,000 barrels a

day. And we engaged countries on the benefits of diversifying their energy supply as a national

security matter.

The approach has worked. The EU put an oil embargo into place in July, and we have certified

that every single one of Iran’s oil importers have either significantly cut or completely ended

their purchases of Iranian oil. We’ve been able to put unprecedented economic pressure on Iran,

while minimizing the burdens on the rest of the world.

Now this strategy influenced our engagement in other places too – for example, Sudan and South

Sudan, where the oil had stopped flowing and getting it going again mattered to both of them

and to us. Both countries’ economies depend on oil. Now most of the oil lies in the new country

of South Sudan. But in order to export that oil, South Sudan needs pipelines and ports, which

Sudan controls. The two countries were fighting over how much money South Sudan would pay

to Sudan to use that infrastructure. They were so far apart, a compromise seemed impossible.

So the United States stepped up our engagement in support of the African Union and the United

Nations to avoid a return to war between the two countries, to help boost their economies, and to

restart oil production at a critical moment for the world’s oil supply.

This past August I flew to Juba, the capital of South Sudan, to urge the parties to recognize

that a percentage of something is better than a percentage of nothing. And a month later, they

signed a cooperation agreement, and it was ratified by the two parliaments this week. Now the

situation is still fragile, and there are many other difficulties that they have to work out between

themselves. But this was a step forward, and I want to commend both sides for their leadership

and courage.

We’ve also worked intensively to support Iraq’s energy sector. In 2010, Iraq produced about

2.3 million barrels of oil each day. Today, that number is 3.2 million. And Iraq is now the

number two oil producer in OPEC, surpassing Iran. This is a major Iraqi success story, helped

by the Departments of State and Energy. We worked with the Iraqis to identify bottlenecks in

their energy infrastructure, to improve their investment plans, and get more oil to the market.

And there’s no question that Iraq’s increased production has helped stabilize oil markets at this

pivotal moment, and it provides a foundation for a stronger economy to benefit the Iraqi people.

I want to mention one additional diplomatic challenge we’re focused on: how to manage

resources that cross national boundaries. Boundaries are not always clearly delineated,

especially at sea. If oil or gas is discovered in an area two countries share or where boundaries

are inexact, how will they develop it? Earlier this year, after a long negotiation led by the State

Department, the United States and Mexico reached a groundbreaking agreement on oil and gas

resources in the Gulf of Mexico, and we will be sending it to Congress for action soon. The

agreement clearly lays out how the United States and Mexico will manage the resources that

transcend our maritime boundary.

Now, in addition to these examples of energy diplomacy, we’re also focused on our second area

of engagement: energy transformation – helping to promote new energy solutions, including

renewables and energy efficiency, to meet rising demand, diversify the global energy supply, and

address climate change. The transformation to cleaner energy is central to reducing the world’s

carbon emissions and it is the core of a strong 21st century global economy.

But we know very well that energy transformation cannot be accomplished by governments

alone. In the next 25 years, the world is going to need up to $15 trillion in investment to

generate and transmit electricity. Governments can and will provide some of it, but most will

come from the private sector. Now, that’s not only a huge challenge, but a huge opportunity.

And I want to make sure that American companies and American workers are competing for

those kinds of projects. After all, American companies are leaders across the field of energy –

leaders in renewables, high-tech, smart-grid energy infrastructure, bioenergy, energy efficiency.

And in the coming decades, American companies should have the chance to do much more

business worldwide, and by doing so, they will help to create American jobs.

Now, governments can do several things to promote energy transformation, like educate our

citizens about the value of energy efficiency and clean technology. But perhaps the most

important thing we can do is enact policies that create an enabling environment that attracts

investment and paves the way for large-scale infrastructure.

In many parts of Central America and Africa, and in India and Pakistan, USAID supports

training programs to help put power utilities on sounder commercial footing. And the

Millennium Challenge Corporation is negotiating new compacts with several countries that

would help them undertake wholesale, systemic energy reforms. And with the right business

climate, agencies like the Export-Import Bank and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation

can help seal the deals that allow U.S. exports to flow.

As an example, let me tell you what we’re doing with our neighbors in Latin America.

Earlier this year, at the Summit of the Americas, Colombia launched a new initiative it is leading

with the United States called Connecting the Americas 2022. It aims to achieve universal access

to electricity by the year 2022 through electrical interconnection in the hemisphere, linking

electrical grids throughout the hemisphere from Canada all the way down to the southern tip

of Chile, as well as extending it to the Caribbean. The Inter-American Development Bank, the

World Bank, all the countries in the Organization of American States have joined this project. It

stems from a broader effort called the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas, which I

launched in 2010, which has sparked a wave of innovative partnerships across the hemisphere.

Interconnection will help us get the most out of our region’s resources. It seems simple, but

if one country has excess power, it can sell it to a neighbor. The climate variability across

our region means that if one country has a strong rainy season, it can export hydropower to a

neighbor in the middle of a drought. Plus, by expanding the size of power markets, we can

create economies of scale, attract more private investment, lower capital costs, and ultimately

lower the costs for the consumer.

There’s another goal here as well. Thirty-one million people across the Americas lack access

to reliable and affordable electricity. That clearly holds them back from making progress in so

many areas. So one aim of Connect 2022 is to make sure that those 31 million people now do

have power. With this single project, we will promote energy efficiency and renewable energy,

fight poverty, create opportunity for energy businesses, including U.S. businesses, and forge

stronger ties of partnership with our neighbors. It really is a win-win-win, in our opinion.

Now, there’s another aspect of energy transformation that I think is important to mention. To

achieve the levels of private sector involvement that we need, it takes a level playing field so

all companies can compete. But you know very well in some parts of the world, the playing

field is hardly level. Some countries dictate how much national content must be used in energy

production, or they give subsidies to their nation’s companies to give them an edge. And that

can be very challenging for American businesses to break through.

So every day, in many parts of the world, our diplomats are out there fighting on behalf of

American businesses and workers, taking aim at economic barriers and unfair practices. This

September, we achieved a major breakthrough when the members nations of the Asia Pacific

Economic Cooperation community agreed to cut tariffs on 54 key environmental goods, clearing

the way for more trade in clean energy technology.

At the same time that we’re pursuing energy transformation, however, we have to take on the

issue of energy poverty. And that’s the third area of engagement I will mention. Because for

those 1.3 billion people worldwide who do not have access to a reliable, sustainable supply

of energy, it is a daily challenge and struggle. It also runs counter to energy transformation,

because these people are burning firewood, coal, dung, charcoal, whatever they can get their

hands on. They’re using diesel generators, and no electricity is more expensive than that. And

besides, these are dirty forms of energy – bad for people’s health, bad for the environment. But

it doesn’t have to be that way. We have the technology and know-how that can help people

leapfrog to energy that is not only reliable and affordable, but clean and efficient. So energy

transformation and ending energy poverty really do go hand in hand.

The United Nations has launched an initiative called Sustainable Energy For All which aims

to do three things: achieve universal access to modern energy by the year 2030; double both

the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency and the share of renewable energy in the

global energy mix. This year, companies and traditional development agencies together have

committed more than $50 billion in financing for sustainable energy if – and it’s a big if –

governments create the right commercial environment. And so more than 60 countries in Africa,

Asia, and Latin America have begun action plans to bring energy investors to their markets.

These investments will lower the high prices many poor people pay today, as well as increasing

access to sustainable energy and opening new markets for American businesses.

The United States has another initiative that tackles a pernicious aspect of energy poverty:

cookstoves. Nearly 3 billion people – that’s almost half the world’s population – don’t have

access to modern cooking technology. They just have fires, often inside their homes, which

cause toxic air pollution, killing nearly 2 million people – mostly women and children – every

year. Think about that – millions dying because of something as simple, as ordinary, as vital

to their survival as a stove. Now, that’s a problem that we are calling on the world to help us

solve. Three years ago, I launched the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, which is working

with foundations, private companies, and other governments to get clean and affordable stoves

into 100 million homes worldwide by the end of this decade.

And finally, we’re focused on a key factor in both energy poverty and political instability – poor

governance. History tells a frustrating tale. Countries that are rich with energy resources often

have less democracy, more economic instability, more frequent civil wars. They are far more

likely to be ruled by dictators, and oil can embolden those dictators to start conflicts with other

countries. It’s often called the resource curse. But the resources aren’t the problem. It’s greed.

The resources can be used to transform a country’s future for the better, but only if they’re used

the right way for the right purposes. So we need to work to undo the resource curse, especially

now as demand for energy guarantees that more developing countries will become oil exporters.

Some countries that recently discovered oil reserves are Liberia, Sierra Leone, Mozambique.

Not long ago, they were all embroiled in deadly conflicts. Their political situations are still

fragile, so they need support to ensure that their energy resources don’t end up causing more

suffering and trouble than good. So the United States is working with eight new oil and gas-

producing countries to help put into place the building blocks of good governance, including

political institutions, transparent finances, and effective laws and regulations. In Uganda,

for example, we’re helping the government adopt strong environmental protection laws and

regulations because oil and gas development is happening in ecologically fragile areas.

We’re also increasing our support for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, an

international program that promotes transparency and accountability in the oil, gas, and mining

industries. And a year ago, President Obama announced that the United States would join

this organization as a signal of our commitment to this issue, and we are the – only the second

developed country to do so. And through the Cardin-Lugar amendment, the United States is

now the first country in the world to require that our extractive industries companies disclose

any payments they make to any government worldwide, an important step in the fight against

corruption.

So the message we’re sending with all of these efforts, from working to resolve energy-related

disputes to cooperating more with our neighbors on expanding electricity, is this: The United

States is convinced that energy in all its complexity will continue to be one of the defining issues

of the 21st century. And we are reshaping our foreign policy to reflect that.

This is a moment of profound change. Countries that once weren’t major consumers are.

Countries that used to depend on others for their energy are now producers. How will this shape

world events? Who will benefit, and who will not? How will it affect the climate, people’s

economic conditions, the strength of young democracies? All of this is still unknown. The

answers to these questions are being written right now, and we intend to play a major role in

writing them. We have no choice. We have to be involved everywhere in the world. The future

security and prosperity of our nation and the rest of the world hangs in the balance. And all of

us, especially all of you here today, have a stake in the outcome.

So whatever you’re studying here at Georgetown, I hope you’ll follow this issue and maybe

even consider becoming engaged, because the challenges that I’ve briefly outlined will only

grow more urgent in the years ahead, and we need all the smart people we can possibly muster

working to solve them. This will take our nation’s best minds, our most talented public servants,

our most innovative entrepreneurs, and millions of dedicated citizens. But I believe that we’re

up to the challenge, that we can, working together, secure a better future when it comes to energy

supply and energy sustainability, and a future that by meeting those two objectives provides

greater dignity and opportunity for all and protects the planet we all share at the same time.

View Map

View Map