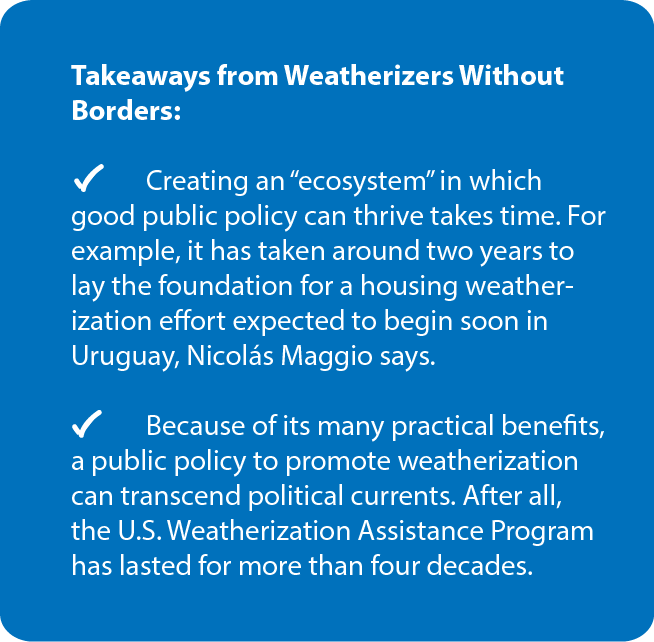

Weatherizers Without Borders is borrowing an idea that has worked for decades in the United States. The U.S. Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), run by the Department of Energy, has enabled millions of homes to be upgraded since it began in the 1970s.

WWB’s president and CEO, Nicolás Maggio, sees no reason why this type of public program—which improves people’s lives, saves energy, and creates jobs—cannot be applied successfully in Latin America. His nongovernmental organization is tapping expertise developed through the U.S. program to get similar efforts off the ground in Argentina and other countries. In 2015, WWB participated in an ECPA forum at the Organization of American States (OAS) on “Energy Efficiency and Weatherization in Low-Income Housing in the Americas,” and Maggio believes the OAS could be an effective partner in these types of efforts moving forward.

So far, Weatherizers Without Borders has implemented small-scale projects in three cities in Argentina—Rosario, Buenos Aires, and Bariloche—and this year it plans to begin work in Montevideo, Uruguay, and Santiago, Chile. In Bariloche, where these efforts are furthest along, the plan is to scale up from 100 houses to 1,000 beginning later this year, bringing together existing local and national resources.

The goal isn’t for Weatherizers Without Borders itself to do housing renovation on a grand scale, Maggio said, but to plant the seed for effective public policy. “This program is optimizing the use of already existing resources,” he said.

In Argentina, Maggio said, the cost of weatherizing a low-income dwelling averages about $1,800 per house, including materials, logistics, labor, training, and other expenses. But that cost can be shared by agencies and organizations with overlapping interests.

Weatherization projects in some cases can tap into public funds already available for housing and energy subsidies, home improvements, job training—even public health. Universities, nonprofit organizations, electric utilities, and development banks also may be interested in donating funds or human resources. So far, Weatherizers Without Borders has established partnerships with local and national governments, CAF- Development Bank of Latin America, Citibank, the Avina Foundation, the U.S. Department of State, and others to start weatherization programs in Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile.

“None of the players can do this alone,” Maggio explained, adding that the challenge is to create a supportive “local ecosystem” and, ultimately, public policies that enable these types of efforts to flourish.

The payoff for individuals is clear. Take Fidelina Llancamil, who lives in a small, bright-green house in a low-income neighborhood on the outskirts of Bariloche, where the weather can be cold and rainy. In a WWB video, she talks about how her leaking roof and thin walls had aggravated her asthma. “In the winter, it was horrible. I didn’t feel like doing anything,” she says.

With support from WWB, CAF, and the municipality of Bariloche, a weatherization team fixed the roof, replaced the sagging ceiling, and added drywall and insulation, among other improvements. “I’m so happy, because everything is nice and warm,” Fidelina Llancamil says in the video. She tells the team, “I’m very grateful for everything you did. You left my house looking so pretty.”

View Map

View Map